- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

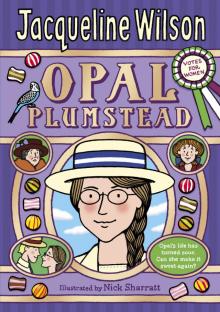

Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

About the Author

Also by Jacqueline Wilson

Copyright

About the Book

Opal Plumstead is fiercely intelligent: a proud scholarship girl, with plans to go to university. Yet her dreams are shattered when her father is sent to prison, and fourteen-year-old Opal must abandon school and start work at the Fairy Glen sweet factory.

Opal struggles to get along with the other workers, who think her snobby and stuck up. But Opal idolizes Mrs Roberts, the factory’s beautiful, dignified owner, who introduces her to the legendary Emmeline Pankhurst and her fellow suffragettes. And when Opal meets Morgan – Mrs Roberts’ handsome son, and the heir to Fairy Glen – she believes she has found her soulmate.

But the First World War is looming on the horizon, and will change Opal’s life for ever.

The brilliant new story from the nation’s best-loved storyteller, starring her most outspoken, fiery and unforgettable heroine yet.

To dear Trish, who typed all thirty chapters for me.

‘DO YOU BELIEVE in ghosts?’ Olivia asked.

We were wandering through the graveyard, trying to find some privacy. Olivia had bought a pennyworth of Fairy Glen toffee chews and we were desperate to eat them. We had to be careful, though. Last week Miss Mountbank had caught us sucking sherbet on our way home from school. She’d pounced on us from a great height, her unfortunate nose more like a hawk’s beak than ever, and had smacked us both on the back so violently that we choked. I spilled sherbet all down my school tunic. It was even worse for Olivia. She snorted in surprise and inhaled half her packet. She coughed uncontrollably, her eyes streaming, slime dripping out of both nostrils.

‘How dare you eat in school uniform, you uncouth little guttersnipes!’ Mounty shrieked.

She gave us detention the next day, shutting us in the classroom and making us write I am disgustingly greedy and a disgrace to the whole school in our best copperplate handwriting. She made Olivia write it out two hundred times. She gave me an extra fifty lines – ‘Because you of all girls should know better, Opal Plumstead.’

I was top of the class. I couldn’t seem to help it. It meant that some teachers liked me and made me their pet, while other teachers like Mounty seemed to resent me bitterly. I tried hard to make the other girls like me, but most of them despised me. They considered it shameful to be such a swot – though what else did they expect from a scholarship girl? I had been dreadfully lonely, but now I had Olivia and she was my best friend.

Olivia Brand came to St Margaret’s last term and didn’t quite fit into any of the little gangs of girls. She wasn’t pretty enough to be popular – she was quite plump so that the pleats on her tunic were stretched out of place. She had a very prominent forehead. She looked as if someone were permanently pulling hard on her long frizzy plait. She wasn’t from a desperately wealthy family. Her father was a buyer at Beade and Chambers, the big department store in town. This meant that Olivia was shunned by the lawyers’ and doctors’ daughters. She was very young for her age, liking to play little-girl games. When she was particularly happy, she would break into a lumbering skip. She was scornfully ignored by the sophisticated girls, who already had proper figures and pashes on boys.

For the first few days of term Olivia had blundered around by herself. She didn’t make any overtures of friendship to me and I was too proud to. It was actually Mounty who brought us together. She paired us up in housecraft and had us sharing a worktop while we made rock cakes. We measured and mixed together, and I grinned sympathetically when Olivia couldn’t resist having a sly nibble at our raisin allowance. We ended up with very bland rock cakes with scarcely any flavouring – but we’d become firm friends.

Now we went round arm in arm and wrote little notes to each other in class and walked home together every day. Olivia was given a weekly allowance. It was supposed to be for books and stationery and ribbons and stockings, but she spent most of it on sweets. She was a generous girl and shared them scrupulously with me, though I didn’t get an allowance of any kind and couldn’t reciprocate.

‘Never mind – you’re my best friend,’ said Olivia. ‘Of course we go even-stevens.’

She shook the bag of Fairy Glen toffees as if it were a tambourine until we skirted the church and threaded our way between the gravestones. I liked reading the quaint inscriptions and admired the stone angels, but Olivia seemed suddenly disconcerted.

‘Do you believe in ghosts?’ she repeated. She was peering around warily, staring at a broken sepulchre.

‘Perhaps I do,’ I said. ‘Shush! Let’s listen for them.’

‘Ghosts don’t talk,’ said Olivia, giggling nervously.

‘I think they might, if we’re very receptive. Hush now, let’s see.’

I made an elaborate show of putting my finger to my lips. Olivia clamped her hand over her mouth to stop herself spluttering. We waited.

A bird sang in the tree, repeating the same three trills again and again. Leaves rustled slightly in the breeze. There was a very distant rumble of traffic. Nothing else.

Then we heard a faint keening sound.

Olivia gasped and clutched me. ‘Did you hear that?’ she whispered.

‘Listen!’ I hissed.

Silence. Then it came again, soft, sad, yearning.

‘Oh, there it is again. Quick, Opal, let’s run. I don’t like it,’ Olivia cried.

Then she saw my face. ‘It was you!’ she said, and thumped me with her satchel.

‘Of course it was me, idiot!’ I said.

I hummed again, and Olivia put her hands over her ears.

‘Stop it! It sounds so creepy. Stop, or I won’t share my toffee chews.’

That shut me up effectively. I mimed buttoning my mouth and hitched myself up on a tomb, swinging my legs.

‘All right, I’ve stopped now. Come on,’ I said, patting the space beside me.

‘I’m not sitting there, right on top of a dead person,’ said Olivia.

‘Well, they can’t do anything, can they? Not if they’re dead.’ I looked again at the broken sepulchre, the stone lid crumbling away. ‘Though perhaps I wouldn’t sit on that one. They might just reach out a very bony hand and grab our toffee chews.’

‘Stop it! I’m warning you, Opal Plumstead. I’ll eat them all myself. Look!’ Olivia sat down on the sandy pathway, undid a banana chew, and stuffed it into her mouth. She crammed in a raspberry chew as well, to emphasize her point.

‘You’re getting your tunic filthy – look,’ I said.

‘Don’t care,’ said Olivia indistinctly, her cheeks bulging.

‘Let’s sit on the grass,’ I suggested.

‘How do I know that the dead people haven’t wriggled about a bit under the grass. The plots are so overgrown, you can’t work out exactly where the graves are.’ Olivia unwrapped

another banana chew. They were my favourites. Sometimes there were only a couple in a whole bag.

‘Pax!’ I cried quickly, jumping off the tomb. I sat down beside her, not caring if I made my own tunic dirty, though I knew Mother would be angry.

Olivia ignored me, slowly unwrapping the banana chew, the tip of her tongue sticking out in anticipation. I edged closer to her, putting my hands up like paws and making beseeching panting noises.

‘All right, you wicked greedy beast,’ said Olivia, and she posted the banana chew into my mouth.

‘Thank you!’ I said, chewing vigorously, my whole mouth filled with the wonderful sweet banana flavour.

‘You’re such a tease. If you weren’t my best friend, you’d be my worst enemy,’ said Olivia. ‘Just don’t go on about g-h-o-s-t-s any more.’

‘I don’t believe in them, not really,’ I said. ‘I think when you’re dead, that’s it. You just moulder away in your coffin.’ I pulled a silly corpse face, and Olivia shoved me again.

‘What about angels?’ she said, looking up at the stone figures around us, all standing on their white tiptoes, wings spread, as if about to fly away. ‘I believe in angels. They’re in Heaven.’

‘I’m not sure I believe any of that any more,’ I said. ‘I think it’s all just a trick to make us meek and good. Never mind if your life is awful now, if you have to toil away twelve hours a day in a factory and live on bread and dripping, you will be rewarded when you die and go to Heaven. Only what if Heaven doesn’t exist?’

‘Shush! You are dreadful. God could smite you down right this instant,’ said Olivia. She looked up fearfully, as if she seriously thought a giant hand were about to punch its way through the clouds and pulverize me.

I swallowed the last of my banana toffee chew and looked at the bag hopefully.

‘Another?’ said Olivia.

‘Oh, yes please!’ I delved into the paper bag and found a strawberry chew this time. ‘Well, you don’t have to worry about Heaven, Olivia. If it does exist, you’ll fly straight there, flippity-flap, because you’re so good.’

‘You will too,’ said Olivia. ‘You’re ever so good. You always come top at school.’

‘Yes, but that’s just because I can do the lessons. That’s nothing to do with being a good person. I’m not at all good at home. My mother says I’m a very bad girl.’

‘Why, what do you do?’ Olivia asked, looking very interested.

‘It’s not really what I do, it’s what I say. I don’t think the same way as Mother and Cassie,’ I said. ‘I’m always saying the wrong thing and vexing Mother. She fusses so over the slightest little thing – and yet she lets Cassie get away with murder. When I point this out, she says I’m just jealous of Cassie and I’ve got an unfortunate nature.’

Olivia sucked at her toffee chew. ‘I wouldn’t blame you if you were a bit jealous of Cassie,’ she said. ‘I mean, I would be if she were my sister.’

I had invited Olivia to tea after we’d vowed eternal friendship. She had clearly been expecting my sister Cassie to be another version of me, only slightly older – pinched and pale and plain, with mouse-coloured hair and little oval glasses. She was taken aback by Cassie, in all her irritating abundance: her long thick wavy fair hair, her big brown doe eyes, her round rosy cheeks, her extraordinary curves, her flamboyant gestures, her peals of laughter. Olivia sat opposite her at the tea table totally struck dumb; she could scarcely eat. She gazed at Cassie as if she were a turn at the music hall. I tried not to mind. I was used to Cassie having this effect on everyone. I found I did mind all the same. Rather a lot.

It hurt that even my very best friend was in awe of Cassie. She looked so dazzling that no one else seemed to notice how infuriating she was – the way she acted all the time, widening her eyes, licking her lips, winding a curl round and round her little finger. I saw her practising in the looking glass, peering at herself this way and that, her hand at her waist to emphasize the curves above and below.

No one else saw her first thing in the morning, scratching herself and yawning, sniffing at yesterday’s stockings to see if they really needed washing, sticking her finger in the jam jar when Mother wasn’t looking. No one else objected to the way she talked. She drivelled on and on about herself, debating what sort of shampoo she should use on her wretchedly abundant hair. She congratulated herself on having naturally pearly skin. She told us all about the fine gentlemen who winked at her admiringly on her way to and from Madame Alouette’s. Mother encouraged her. She still brushed Cassie’s hair for her, a hundred strokes every night, and made her little oatmeal messes to apply to her famous pearly skin. Mother tutted disapprovingly at the tales of winking gentlemen – but she seemed proud of their attention too.

‘You’ve got the looks that will turn every man’s head, Cassie,’ she said, preening as if they were her looks too. ‘But don’t you go wasting yourself on the first Tom, Dick or Harry who comes along. You can aim much higher than any local lad. You just bide your time, my dear. No winking back, no giggling, no saucy remarks. You can’t go getting a reputation now, or no one will want you, stunner or not. You need to act like a little lady at all times.’

‘I’m not the slightest bit jealous of Cassie,’ I told Olivia.

I was lying. I found Cassie incredibly irritating, and I didn’t want to be like her, so lazy and vacant, never wanting to read a book or look at a painting. I certainly didn’t envy her working at Madame Alouette’s milliner’s shop, stitching away at flimsy silks and satins and having to bob and curtsy to fancy ladies. I didn’t want to be her in the slightest – but in my secret heart of hearts I had to admit I wanted to look like her. I didn’t want the attention of all the silly young men. I didn’t even want Mother fussing over me. But I did wish that Father would look at me with such helpless admiration in his eyes. He’d always seemed dazzled by Cassie too. But poor Father was so sad and self-absorbed now, he didn’t look at any of us when he was at home. He kept his head bent and his eyes lowered and he hardly ever spoke.

‘Cassie will make a lovely angel,’ said Olivia. ‘I can just see her in a long white dress with a halo above her gorgeous hair.’

‘Cassie’s no angel,’ I said sourly, but the image was in my head too. I rummaged in my school bag and found a notebook. I started sketching, showing Cassie with a devout expression, eyes wide, lips pursed, a halo attached to her hair like a little gold sunhat. I exaggerated her hair, letting it tumble all the way down to her bare feet, and I drew several young men prostrated before her, kissing her toes.

Olivia peered at my page and spluttered with laughter. ‘Oh, Opal, you’re such a hoot. That’s exactly Cassie. You’re so good at art.’

‘Tell that to Miss Reed,’ I said.

I loved to draw and paint, but art was my worst subject at school. I was used to getting ten out of ten in all my other lessons, but Miss Reed awarded me seven at best, and often gave me a disgraceful nought out of ten. She hated the way I drew.

‘You’ve got the skills but you don’t apply yourself seriously. Art isn’t a joke, Opal Plumstead,’ she said. She had some problem with her teeth and always unintentionally spat a little saliva at you if you stood face to face with her.

I did take art seriously, but I hated drawing the boring vases and boxes and leaf sprays she arranged as still-life compositions. I tried to sketch each object accurately, but my pencil had a will of its own. I executed the vase perfectly, but drew an exotic genie leaping out of it in a puff of smoke. I attempted the box and mastered its perspective, but then drew ropes of beads and gold coins spilling from its carefully shaded depths. I managed the leaf spray, noting every line on each separate leaf, then drew a miniature Jack climbing up the beanstalk I’d grown for him.

‘I will not have you drawing this nonsense!’ Miss Reed spluttered, and failed me each time. In fact, she sent me directly to Miss Laurel, the headmistress, when I drew the genie, because I’d pictured him in a loincloth and she felt this was obscene.

&nb

sp; Miss Laurel lectured me at length, though the corners of her mouth had twitched when she saw my offensive drawing. ‘You’re a bright girl, Opal, and you generally work hard. Why do you have to be deliberately subordinate in your art lessons?’ she asked.

I pondered. It was easy enough to do the work properly in all my other lessons. It was as if I set a little machine clicking away in my head. It solved the mathematical problem of the men digging holes in a field; it parsed the passage of English; it could trace the rivers and lakes in Africa without wavering. But somehow I couldn’t draw mechanically. My mind took over and wanted its own way. I considered trying to say this to Miss Laurel but knew she wouldn’t consider this an adequate explanation.

‘I’m very sorry, Miss Laurel,’ I said instead.

She shook her head at me. ‘Then stop plaguing poor Miss Reed,’ she said. ‘And you’re simply short-changing yourself, you silly girl. You need to get perfect marks in every subject if you want to matriculate. You seem like an ambitious girl. This is your chance to better yourself. You don’t have to end up as a shop girl or a servant. If you really worked hard, you could even be a teacher at St Margaret’s one day.’

A teacher like Miss Reed, Miss Mountbank, Miss Laurel herself! I didn’t want to be a teacher, though everyone seemed to assume that this would be my ideal career, because I was good at lessons and had the knack of passing exams.

‘What do you want to be when you grow up, Olivia?’ I asked now.

She took another toffee chew and threw one to me. ‘Mm, chocolate! I think I’ll have my own sweet emporium. Imagine being able to munch and crunch all day long. No, I’ll marry a man with a sweet shop, and then I won’t have to stand on my feet and serve people. I’ll just lounge on the sofa with a huge box of chocs and be the lady of the house. And I’ll have two children, a boy and a girl, and we’ll keep several servants to do all the work and it will be so jolly.’

‘You’ll be jolly fat, lying around all day stuffing yourself with sweeties,’ I said, pulling her plait.

‘Don’t,’ said Olivia, looking fussed. ‘Do you think I’m fat now?’

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

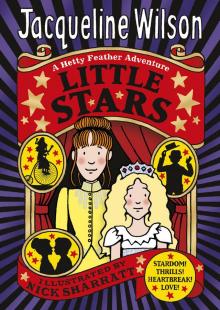

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets