- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

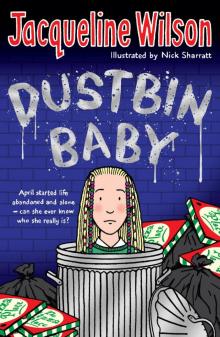

Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Epilogue

Quick Quiz

Things to Think About

Read on for the first two chapters of MY SISTER JODIE.

About the Author

About the Illustrator

Also by Jacqueline Wilson

Copyright

About the Book

My name is April. April Showers – that’s my nickname at school now.

At least it’s better than April Fool. And it’s much, much better than Dustbin Baby . . .

I don’t know where I came from, or who I really am. All I know is that I was abandoned as a tiny baby in a rubbish bin. I’m safe with my foster mother now – but if only I could find my real mother, somehow . . .

To Emily Eaves

I wonder if you’ve ever had to draw your own family tree at school? It’s generally a fun thing to do, especially if you can design it like a real tree, with branches here and there. You can draw a snake slithering round the branch representing your pesky little brother, cute squirrels scampering along the branches symbolizing your favourite cousins and maybe an owl with glasses roosting on the branch for your wise old uncle. But whether you do this funny version, or just use plain lines and your best handwriting, it’s generally easy to construct.

I could start with me at the bottom, then have my mother Biddy and my father Harry holding hands above me, and then above them my maternal grandparents, George and Hilda Ellen, and my paternal grandparents, Harry and Dorothy. After that it gets a bit hazy, but at least it’s a start.

What would happen if you couldn’t make that start? How would you feel if you could only put your name on the page? That’s what it’s like for April, the girl in Dustbin Baby. She’s not even sure that’s the name her mother would have chosen for her. She doesn’t have a clue who that mother is. April was abandoned in a dustbin the moment she was born, bundled up and left to die. Thank goodness she cried hard and someone heard and rushed her to hospital. This happened on April 1st, All Fool’s Day, when you play jokes on people. April’s life hasn’t been much of a joke though. She’s been sent here, sent there, fostered out, stuck in a children’s home, boarded in a special school, until she doesn’t know where she is. She doesn’t know who she is.

Dustbin Baby takes place all in one day, this momentous fourteenth birthday when April sets out to find herself. I think we all go through a stage of feeling a little odd and alienated from our families at this age. It must be so much harder if you feel you haven’t got any family at all.

I felt very close to April when I was writing her story and I struggled hard to make sure she had a happy ending.

Let’s begin with a happy ending.

I sit here in the warm, waiting. I can’t eat anything. My mouth is too dry to swallow properly. I try sipping water. The glass clanks against my teeth. My hand is trembling. I put the glass down carefully and then clasp my hands tight. I squeeze until my nails dig in. I need to feel it. I need to know that this is real

I think people are staring at me, wondering why I’m all on my own. But not for much longer.

Please come now.

Please.

I look out the window, seeing my own pale reflection. And then there’s a shadow. Someone stares back at me. And then smiles.

I smile too, though the tears are welling in my eyes. Why do I always have to cry? I mop at my face fiercely with a napkin. When I look back the window is empty.

‘April?’

I jump. I look up.

‘April, is it really you?

I nod, still crying. I get clumsily to my feet. We look at each other and then our arms go out. We embrace, hugging each other close, even though we are strangers.

‘Happy birthday!’

‘This is the best birthday ever,’ I whisper.

It’s nearly over – and yet it’s just beginning.

1

I ALWAYS HATE my birthdays. I don’t tell anyone that. Cathy and Hannah would think me seriously weird. I try so hard to fit in with them so they’ll stay friends with me. Sometimes I try too hard and I find myself copying them.

It’s OK if I just yell ‘Yay!’ like Cathy or dance hunched-up Hannah-style. Ordinary friends catch habits from each other easily enough. But every now and then I overstep this mark in my eagerness. I started reading exactly the same books as Cathy until she spotted what I was doing.

‘Can’t you choose for yourself, April?’ she said. ‘Why do you always have to copy me?’

‘I’m sorry, Cathy.’

Hannah got irritated too when I started styling my hair exactly like hers, even buying the same little slides and bands and beads.

‘This is my hairstyle, April,’ she said, giving one of my tiny beaded plaits a tug.

‘I’m sorry, Hannah.’

They’ve both started sighing whenever I say sorry.

‘It’s kind of creepy,’ said Cathy. ‘You don’t have to keep saying sorry to us.’

‘We’re your friends,’ said Hannah.

They are my friends and I badly want them to stay my friends. They’re the first nice normal friends I’ve ever had. They think I’m nice and normal too, give or take a few slightly strange ways. I’m going to do my best to keep it like that. I’m never going to tell them about me. I’d die if they found out.

I’ve got so good at pretending I hardly know I’m doing it. I’m like an actress. I’ve had to play lots and lots of parts. Sometimes I’m not sure if there’s any real me left. No, the real me is this me, funny little April Showers, fourteen years old. Today.

I don’t know how I’m going to handle it. It’s the one day when it’s hard to pretend.

Marion asked me last week if I wanted to do anything special. I just shook my head, but so emphatically that my face was hidden by my hair.

Cathy had a sleepover for her fourteenth birthday. We watched spooky videos and one hilarious rude one that gave us the most terrible giggles and put us off having sex for life.

Hannah had a proper party, a disco in a church hall decked out with fairy lights and candles to try to give it atmosphere. There were boys too, but only Hannah’s brother and his friends and a few totally sad guys in our year. Still, it was great fun.

I loved Cathy’s birthday. I loved Hannah’s birthday. It’s mine that is the problem. I just want to get it over and done with.

‘Are you sure you don’t want a party?’ Marion asked.

I can just imagine the sort of party Marion would organize. Charades and Pin-the-Tail-on-the-Donkey and sausages on sticks and fruit punch, like way back when she was young.

Maybe that’s not fair.

I’m sick of being fair.

I’m sick of her.

That’s so mean. She’s trying so hard.

‘Perhaps you and I could go out for a meal somewhere?’ she suggested, like it would be a big treat.

‘No, honestly, I don’t want to make a big deal of my birthday,’ I said, yawning, as if the whole subject simply bored me.

Marion’s no fool. ‘I know birthdays must be difficult for you,’ she said softly.

‘No, they’re OK. I’m OK,’ I insisted. ‘I just don’t want you to make

a fuss about it.’

She swallowed. Then she looked at me sideways. ‘I take it presents aren’t making too much of a fuss?’ she said.

‘I like the sound of presents,’ I said, snapping out of my sulks.

I looked at her hopefully. I’d hinted enough times. ‘What are you giving me?’

‘You’ll have to wait and see,’ said Marion.

‘Give me a clue, please!’

‘Absolutely not.’

‘Go on. Is it . . . is it . . .?’ I gestured, holding one hand up to my ear.

‘You’ll have to wait and see,’ said Marion, but she smiled broadly.

I’m sure I’ve guessed right. Even though she’s moaned and groaned about them enough.

Marion wakes me up with a birthday breakfast in bed. I don’t actually ever want to bother with breakfast but I sit up and try to look enthusiastic. She’s poured far too much milk on my cornflakes but she’s added strawberries too, and she’s put a little bunch of baby irises in a champagne flute to match the willow pattern china. There’s a present on the tray, a neat rectangle, just the right size.

‘Oh Marion!’ I say, leaning forward, almost ready to hug her.

Milk splashes all over the sheets as the tray tilts. ‘Careful, careful!’ Marion goes, snatching the present to safety.

‘Hey, it’s mine!’ I say, taking it from her. It feels a little light. Maybe it’s one of those really neat tiny ones. I undo the ribbon and rip off the paper. Marion automatically smoothes the paper and winds the ribbon neatly round and round her fingers. I take the lid off the cardboard box – and there’s another smaller box. I take the lid off this box and find another even smaller box. Too small, surely.

I remember someone playing a trick on one of the kids in Sunnybank. They opened up box after box after box. There was nothing at all in the matchbox at the end and everyone laughed. I did too, though I wanted to cry.

‘Go on, open the next box,’ says Marion.

‘Is it a joke?’ I asked. Surely she wouldn’t play games with me like that?

‘I didn’t want you to guess what it was too easily. But I think you know. Open it, April.’

So I open it. It’s the last box. There’s a present inside. But it’s the wrong present.

‘It’s earrings!’

‘Do you like them? They’re blue moonstones. I thought they’d bring out the blue of your eyes.’

I barely hear her. I feel so disappointed. I was sure she was giving me a mobile. She smiled when I gestured . . . Then I realize. She thought I was pointing at my newly-pierced ears.

The fancy earrings are a peace-offering. She made such a fuss when Cathy and Hannah egged me on one Saturday and I got my ears pierced in Claire’s Accessories. You’d have thought I’d had my tongue pierced the way she was carrying on.

‘What’s the matter?’ she asks. ‘Don’t you like the moonstones?’

‘Yes. They’re lovely. It’s just . . .’ I can’t keep it in any more. ‘I thought I was getting a mobile phone.’

Marion stares at me. ‘Oh April! You know what I think about mobiles.’

I know all right. She’s gone on and on and on about all these stupid brain tumour scares and the whole big bore social nuisance factor. As if I care! I just want my own mobile like every other girl my age. Cathy got a mobile for her fourteenth birthday. Hannah got a mobile for her fourteenth birthday. Every girl everywhere gets a mobile for her fourteenth birthday, if not before. All the Year Nine girls have got mobiles. And most of Year Eight.

I feel like I’m the only one anywhere without any means of communication. I can’t natter or send funny text messages or take calls from my friends. I can’t join in. I’m the odd one out.

I always am.

‘I wanted a mobile!’ I wail like a baby.

‘Oh for God’s sake, April,’ says Marion. ‘You know perfectly well what I think about mobiles. I hate them.’

‘I don’t!’

‘They’re an absolutely outrageous invention – those ridiculous little tunes tinkling everywhere, and idiots announcing “Hello, I’m on the train” – as if anyone cares!’

‘I care. I want to keep in touch with my friends.’

‘Don’t be silly. You see them every day.’

‘Cathy is always sending text messages to Hannah and she sends them back and they’re always laughing away together and I’m always left out – because I haven’t got a mobile.’

‘Well, that’s tough, April. You’ll just have to learn to live with it. I’ve told you and told you—’

‘Oh yeah, you’ve told me all right.’

‘Please don’t talk in that silly sulky tone, it’s incredibly irritating.’

‘I can’t help it if you think I’m irritating. I don’t see that it’s so terrible to want a mobile phone when it’s what every single teenager in the entire world owns without question.’

‘Don’t be so ridiculous.’

‘Why is it so ridiculous? I just want to be like my friends. Cathy’s got a mobile. Hannah’s got a mobile. Why can’t I have a mobile?’

‘I’ve just told you why.’

‘Yes, well, I’m sick of you telling me this and telling me that. Who are you to tell me all this stuff? It’s not like you’re my mother.’

‘Look, I try—’

‘But I don’t want you to!’

My mouth says it all of its own accord. There’s suddenly a silence in the room.

I didn’t mean it.

Yes I did.

Marion sits down heavily on the end of my bed. I look at my breakfast tray. I look at my blue moonstone earrings.

I could say I’m sorry. I could say sweet things to her. I could eat up my cornflakes. I could screw my new earrings into my ears and give Marion a big kiss and tell her I just love the blue moonstones.

Only I wish they were a mobile phone. I don’t see why that’s so wicked. I mean honestly, a mobile! Doesn’t she want me to keep in touch with everyone?

Maybe she wants me all to herself. Well, I don’t want her.

I get up, I leave my breakfast tray, I go into the bathroom, locking the door on Marion. I want to shut her out of my life. I don’t want to wear her silly little moonstone earrings. I was into fancy earrings months ago, when I kept nagging to have my ears pierced. Can’t she keep a track of things? I am so sick of her and the way she never manages to get things right.

I get washed. I get dressed. Marion’s gone downstairs. I wish I could sidle out of the house without having to face her. I don’t see why she always has to make me feel so guilty. It’s not my fault. I didn’t ask her to take care of me. I’m not going to wear the earrings. I don’t want those twinkly little-girly earrings clogging up my earlobes. I’m sick of thinking about her and her feelings.

She’s bending down by the front door, picking up the post. My heart leaps. There are three birthday cards – but not the one I’m looking for. Though it’s silly, she doesn’t know my address. Maybe she doesn’t even know my name. How could she ever get in touch?

Marion is watching me. Her face is all creased up with sympathy. This makes me feel even worse. ‘April, I know it’s hard for you. I do understand.’

‘No, you don’t!’

She presses her lips together until they nearly disappear. Then she breathes heavily through her nose like a horse.

‘I know this is a difficult day for you but there’s no need to shout at me. You’re acting like a sulky little brat. You haven’t even thanked me properly for the earrings.’

‘Thank you!’

It comes out even more rudely than I intended. I feel tears of shame prickling my eyes. I don’t want to hurt her.

Yes I do.

‘I’m sick of having to say please and thank you all the time and acting all prissy and posh. I don’t want to be like you. I just want to be me,’ I say, and I barge past her, out the front door, off to school. I don’t even say goodbye.

I don’t want to think about Marion any more b

ecause it makes me feel so bad. I’ll wall her up right at the back of my mind. There are a lot of other people squashed in there in the dark.

I think about me. I don’t know how to be me when I’m by myself. I don’t know who I am. There’s only one person who can tell me and she’s got no way of getting in touch.

I think about it.

I go into the paper shop on the corner. Raj grins at me. ‘Hi, April.’

I walk past the chocolate, the crisps, the fizzy drinks. I look at the newspapers in neat black-and-white rows. The Times. That’s the one with the Personal column. We divided it up between us in Media Studies and had to analyse each section.

I can’t really search through the whole paper looking for it. Raj has pained little messages pinned up on his shelves. ‘I am not a lending library. No looking without purchasing’.

So I’ll purchase. Raj pulls a funny face. ‘Getting all serious and intellectual, April?’ he says.

‘That’s right,’ I say.

‘It’s a joke, right? For April Fool?’

‘No, I really want to buy it.’

‘You girls,’ says Raj, as if I’m playing an elaborate trick on him.

He doesn’t know, but I don’t ever play April Fool jokes. No wastepaper baskets balanced on top of doors, no drawing pins on chairs, no ‘Watch out, what’s that behind you?’. On my birthday I always feel there’s really something about to fall on me, that someone’s creeping up on me. I long for it to happen.

I give Raj the money for the paper. He peers at the coins suspiciously, checking whether they’re chocolate. I’ve fooled him all right. My trick is that there’s no trick.

There’s no message either. I lean against the wall outside the shop and struggle with the flapping pages. April is a windy month. I wish I’d been born at another time of the year. What a birthday – April Fool’s Day. Talk about a sick joke.

Some of the messages in the Personal column could be cryptic jokes. They make no sense to me. But there’s nothing from her. No ‘Happy Birthday – I always think of you on April 1st’. Does she? I always think of her. I don’t know what she’s really like of course. But I can imagine.

I’m good at imagining.

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

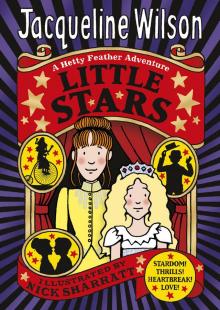

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets