- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

Hetty Feather Page 10

Hetty Feather Read online

Page 10

I was right to be so cautious. Once I had my pinafore and dress and drawers off, standing shivering in my shift and stockings, the matron darted at me, snatched my rag baby and threw her in the basket too.

'She's not clothes! She's my baby!' I protested, though it was hard to talk distinctly with the sixpence wedged in my cheek.

'It's nasty and dirty. And you're not allowed dollies here.'

'But I can't sleep without her!'

'Then you will have to stay awake,' said the matron.

She pulled the shift over my head, plucked my stockings from my feet, lifted me up and plunged me into the bath. Then she took a cake of red carbolic soap and started scrubbing me viciously. I wriggled and squirmed at the indignity, especially when she started washing my long hair, digging her fat fingers into my scalp and kneading it as if my head was a ball of dough. I put my hands up, trying to protect my poor head. My fingers scratched her wrists and she dug harder, furious.

'Keep still, you fiery little imp,' she said, lathering me into a foam. She fetched another jug to rinse the suds away. 'This will quench that fire!' she said, pouring icy cold water over me.

I gasped in shock and would have screamed at her, but I had to keep my mouth stoppered because of the sixpence. Then she hauled me out onto the cold floor and wrapped a thin towel round me.

'Well, dry yourself, child, hurry up, hurry up!'

When I was halfway dry she sat me on a stool and picked up a pair of scissors. I started trembling. What did she intend to do now? Cut off my fingernails? Cut off my fingers?

She attacked my head with a hairbrush, smoothing out all the tangles so that my hair fell in a silky curtain past my shoulders – and then she started snip-snip-snipping, cutting my hair off right up to my ears.

'Oh, please don't cut my hair!' I begged, but she paid no heed. She snipped until my hair was shorter than a boy's and I was covered in damp red tendrils. She brushed them off me with the towel and then fetched another basket, the clothes inside this one neatly folded.

'This will be your clothes basket, Hetty Feather. You are to keep your clothes in it at night, and woe betide you if you rumple them.'

She pulled out boots and stockings and bade me put them on. The stockings were stiff and bunched at the toes with repeated darning, and the boots were much too big for my small feet. I told Matron, but she didn't appear to care.

'Put your dress on now – the right way round, you silly child. I will tie your apron for you.'

I hesitated. Where were my new undergarments? I saw something white in my basket, but it was simply a strange old-fashioned cap. There was no shift, no drawers, nothing!

I sidled over to my old clothes.

'Leave them alone! They're going to be disposed of straight away.'

'But, miss – Matron – I have no drawers!' I said, agonized.

The matron's pig face went even pinker. 'You do not wear such garments here,' she said. 'Now put that dress on at once.'

I stuck my poor shorn head through the stiff brown serge. It felt hard and scratchy against my scrubbed skin. She did up my buttons at the back for me, tied on the apron, and then stuck the cap upon me.

'There!' Matron marched me over to a speckled mirror above the stone slab sinks. 'Respectable at last!'

I stared at the forlorn figure in the mirror. Was that weird little creature in the cap really me? I shook my head violently, but the girl in the mirror shook her head back at me.

'Now you will join the other infant girls. Come with me.'

I hung back, fidgeting. 'Please, miss – Matron – I need the privy,' I blurted.

She consulted the watch pinned to her chest. 'The infant relief break is not for another hour. You will have to wait.'

'But I need to go now! Please, I'm nearly wetting myself!'

She sighed impatiently. 'The privies are outside in the yard. I'm not trailing you all the way there. You will have to use a chamber pot. Go in that little room and be quick about it. You must learn to control your bladder as well as your temper, Hetty Feather.'

I ran into the room, selected an ugly pot and sat on it, trembling. What sort of a madhouse was this? I put my fingers up under my cap and felt the shorn ends of my hair. I gave a little sob. Even if I managed to run away back to Jem, maybe he wouldn't love me any more because I looked such a fright.

'Hurry up, child!' Pigface grunted outside.

Safe behind the door, I took the sixpence out of my mouth, stuck out my tongue and waggled it at her. Then I hid the sixpence in my new tight cuff and jumped up from the pot.

'Now wash your hands!' she said as I came out of the little room. 'Dear goodness, do you know nothing of hygiene?'

I didn't think it at all hygienic to run around without underwear. I wondered if the matron wore drawers herself. I imagined her big piggy-pink bare bottom.

'What are you smirking at?' she said suspiciously.

I lowered my eyes and shook my head. 'Nothing, Matron.'

'Then come along with me. You will join your class at their afternoon tasks.'

She took hold of me by the wrist. I looked back at the little basket of my Sunday clothes, so lovingly washed and pressed by Mother. They were all in a muddy jumble now, my poor rag baby sprawling on top, arms and legs akimbo.

'Come on! You've no need of those nasty old clothes any more, I've told you that already,' said Matron Pigface.

'Mayn't I just kiss my baby goodbye?' I begged.

'I've never heard such nonsense. It's only a bundle of rags!' she said, and she would not let me.

I pictured my poor baby so forlorn without her mother. I heard her wailing, abandoned in the basket. I wished she was little enough to hide about my person, like the sixpence. But there was nothing I could do. I had to leave her there, tumbled about in my clothes. I never saw her again.

As Matron Pigface marched me along to my class, I thought at least I would meet up with Gideon again – but there was no sign of him. I was thrust into a room of some forty or fifty girls of five or six or seven, but there was not a single little boy. The girls were sitting at small wooden desks, all startlingly similar in their white caps and mud-hued dresses. They all stared hard at me and then whispered. I shifted from one sorely-shod foot to the other, feeling so shy and strange.

'This is Hetty Feather,' said Pigface.

Several of the little girls giggled. My hands clenched into fists.

'Thank you, Matron Peters,' said a starch- aproned nurse at the front of the class. She wasn't pink and pig-faced, she wasn't grim and pale. This nurse had rosy cheeks and dimples and wisps of curly hair escaping from her cap. She was as sweet and fresh-faced as Rosie or Eliza or any of the village girls. She smiled at me.

'I would watch this one. She's got a very contrary way with her. Redheads are always little vixens,' said Matron Pigface Peters. 'She needs that temper quelled. Spare the rod and spoil the child, remember!' She shorted, and then waddled out of the room, her stays creaking loudly.

'Hello, Hetty dear,' said this new nurse, beckoning to me.

I crept up to her desk. I saw a leather strap lying across it. Oh Lordy, was she about to punish me already?

No, she leaned towards me and said gently, 'Do not look so fearful, child. It must seem very strange your first day here, but I promise you will soon get used to life at the hospital. You seem very small. Are you turned five yet?'

'I am almost six,' I said.

'Excellent! Then I think you are old enough to learn how to darn, Hetty.' She brought out a stocking and a needle and wool from her desk. 'Did your foster mother teach you how to sew, Hetty?' she asked.

The word Mother made my eyes well up. I shook my head wordlessly.

'Then I will show you.'

She threaded the big needle, squeezing the end of the wool over with practised skill, and then put her hand inside the stocking. She started looping the wool across the hole in neat lines.

'There, do you see?'

Then she started

weaving the wool the other way, making the neatest, smoothest patch. I watched, fascinated in spite of my misery. My head was itching horribly after my haircut and I put up my hand to scratch, knocking my cap sideways.

'Try not to scratch, dear, it's not very ladylike,' said the nurse. She put down the beautifully darned stocking and took my cap off. She smoothed my poor shorn hair, drying now, and sticking straight up in the air.

'My goodness, I think I remember you!' she said. 'You were the smallest baby I'd ever seen – and you had the reddest hair!'

She was the nurse who had cradled me when I was newborn and wouldn't suck properly! She was dear kind Winnie, though now she told me to call her Nurse Winterson. She bade me sit on a stool beside her while I struggled to darn a stocking myself. I badly wanted to impress this gentle nurse and show her I could act like a big girl, even though I was so small – but I couldn't get the hang of darning at all.

I pulled the needle too hard so that it came right off the wool, and then I had no end of bother re- threading it. Nurse Winterson kept threading it for me, and patiently guided my hands, but I could barely do a single stitch. I was in such a state I came near to flinging the stocking upon the floor.

I heard whispers and giggles from the other girls. Every now and then I looked up from my wretched task and glared at them. They all seemed identical at first, but when I peered harder I saw some had rosy cheeks and some had pale; some had snub noses and some had freckles; some had blue eyes and some had brown. There was one girl with a pair of spectacles on her nose who had her head bent right over her stocking, examining her stitches. There was something familiar about the bend of her head, the little frown lines above her nose . . .

'Martha!' I cried out. I jumped to my feet in my excitement, my stocking rolling to the floor. 'Oh, Martha, it's truly you!'

I ran down the line of desks and threw my arms around her neck. The other little girls squealed and squawked at my behaviour. Martha herself edged away from me, looking alarmed.

'Hetty, Hetty!' Nurse Winterson came speeding after me. 'You must not be so passionate, child! And you have to learn to stay still in your seat like a good little girl.'

'But it's Martha, my sister Martha!' I cried. Martha still looked dazed. 'Tell them, Martha! I am your sister Hetty.'

Martha blinked her poor squinting eyes. 'Hetty?' she said. 'Did I have a sister Hetty?'

'Oh, Martha, you can't have forgotten me!' This was such a terrifying thought that I burst into floods of tears.

'Oh yes,' said Martha, nodding now. 'You were the little one who cried a lot.'

She really seemed to have no other clear recollection of me. The girls on either side of her giggled, and Martha blushed and wriggled further away from me, clearly embarrassed.

I let Nurse Winterson lead me back to my chair. I picked up my stocking and applied myself to darning, but tears kept brimming and the stocking blurred in my hand. I was so shocked that Martha had barely remembered me, her own sister. Did she not remember any of us – Rosie, Eliza, Nat, Jem? Surely she must remember Saul. I wondered when we were to meet up with all the boy foundlings.

A bell rang at four and all the other girls stuffed their stockings into workbaskets in their desks. Nurse Winterson took my poor cobbled stocking and held it up, examining my enormous stitches.

'Oh, Hetty, you've sewn the sides together! How could anyone get their foot into this stocking?' she said, wafting it gently in front of me.

The other girls giggled and grinned. I felt my cheeks turn fiery red.

'We will try again tomorrow,' said Nurse Winterson. 'Cheer up, Hetty. We will make an expert seamstress of you yet. Now, run and play outside with the other girls.'

I followed them forlornly. I did not want to play with any of them and I was sure they did not want to play with me. They scurried along the corridor and down the stairs, calling to each other, though they subsided abruptly when another nurse appeared on the stairs. She clapped her hands crossly.

'Quietly, girls! No talking at all until you get outside,' she said. She noticed me skulking at the top of the stairs. 'Come along, child, don't loiter. The girls' playground is down the stairs and through the big door.'

'Please, miss – Nurse – mayn't I go to play with the boys?' I asked.

She drew herself up, hands on her hips. 'Of course not, you bold little girl!'

'But I need to see my brother Gideon. He will be so wretched without me. Please, Nurse, I need to see my brother so badly,' I begged.

Nurse Winterson came and stood beside me, her hand on my shoulder. 'Perhaps it will help Hetty settle down if we let her see her foster brother for a few minutes,' she suggested.

But the other nurse shook her head firmly. 'Really, Winnie! Will you never learn? You can't afford to be so soft-hearted with the children. If we change a rule for just one child, they will all be clamouring for special privileges.' The fierce nurse turned to me. 'Now run away and play or you shall be whipped!'

I ran because I certainly did not want to be whipped. The other girls were playing games of tag, or strolling around together arm in arm, or sitting in little circles telling secrets. I did not have anyone to play with.

I peered around desperately for Martha. She was walking with a girl on either side, all of them singing a song. I sidled nearer until I was walking two steps behind. One of the girls craned round.

'Stop following us!' she said.

'I'm not following you, I'm following my sister,' I said fiercely. I ran round them and stood right in front of Martha. Her eyes blinked anxiously behind her spectacles.

'I am so happy to find you, Martha. I have so much news to tell about Mother and Father and dear Jem, and did you know that Gideon is here too, we travelled together in a big steam train, and there is a new little baby Eliza, and do you ever see Saul, and that horrid matron took all my best clothes and my rag baby, and I've been to a real circus and ridden on a white horse . . .' I was babbling now, trying to get some kind of reaction from poor Martha. She looked bewildered.

'I don't really remember,' she said. 'That was long ago. I only remember now.'

'But now is so horrid!' I said, starting to cry again.

'Don't cry!' said Martha. 'Please don't. It hurts my head. All right, Hetty, you can walk with us. This is Elizabeth and this is Marjorie.'

They both sighed, but let me trail after them. When they resumed their silly song, all tra-la-la's and tootle-tootles, I did my best to imitate them.

Nurse Winterson rang the bell at the end of playtime. She smiled at me. 'There, Hetty, you've made friends already,' she murmured to me.

She didn't understand that Martha was simply trying to be kind because of our dimly remembered kinship – and Elizabeth and Marjorie certainly did not wish to be friends.

We were all marched to the privies, where we took it in turns to relieve ourselves, ten girls at a time. We then washed our hands with the horrible carbolic soap. I could barely reach up to the basin and got water right up my arms, wetting the uncomfortable cuffs on my sleeves. My hidden sixpence was rubbing a bruise on my skin, but I bore the pain proudly.

Then we were marched again – one two, one two, one two – into a large echoing dining room set with very long tables. The little girls scrambled onto benches. I stood bewildered in the crush and lost my chance of sitting next to Martha. I had to squash right on the end of a bench next to a fierce- looking fair girl with a high forehead, who dug me hard with her elbow when I took a bite of the bread on my plate.

'You're not allowed, not yet!' she hissed.

We had to wait as endless lines of big girls filed in too, until the whole hall was filled with girls girls girls, all scarily alike in their brown dresses and white caps.

My stomach was rumbling because I'd missed having any dinner on this most terrible day, but I still had to wait until Matron Pigface said, 'Let us say grace, girls.'

I did not understand and mumbled, 'Grace.' The fierce girl snorted derisively.

&n

bsp; 'For what we are about to receive may we be truly grateful, amen,' she chanted with all the others.

We'd never said grace at home, we'd just grabbed our bowls from Mother and started spooning, but I was truly grateful for my slice of bread and my wedge of cheese. I wolfed them down in four bites and waited. And waited. There didn't seem to be anything else, apart from a mug of watered-down milk.

I was a country child. We might have been poor but Mother believed in giving us big platefuls and our milk was always creamy rich. I wondered if my helping was minute because I was the smallest girl here, but when I peered around, I saw that even the very big girls with chests filling out their tippets had the same size slices.

I wondered how I was going to bear the enormous emptiness inside my stomach. I didn't realize that it wasn't simply hunger, though that was a small part of it. An entire loaf of bread and a round of cheese could not have eased the ache of my loneliness.

I wondered how Gideon was faring in the boys' wing, unable even to ask for what he wanted, and my tears brimmed again. The fierce girl beside me took no notice, but a big girl with long plaits came over to our table.

'You can go and play for a little, you babies,' she said. She stopped in front of me. 'Oh dear! Are you feeling monk?'

'She's new today,' said the fierce girl. 'They're always monk when they're new.'

I didn't know what monk meant exactly, but I certainly felt it.

'Don't cry, baby,' said the big girl, and she lifted her own apron and dabbed at my eyes. 'You're so weeny. Don't worry, I'll look out for you. My name's Harriet.'

'My name's Hetty.'

'My, they're very similar. Some of the girls call me Hatty.'

'I had long hair like yours,' I said, taking hold of her long silky plaits. 'But that nasty horrid matron with a pig face cut it all off.'

Harriet giggled but put her hand over her mouth. 'You mustn't talk like that about the matron! She wasn't being deliberately nasty or horrid, all the new girls have their hair cut off, it's the rule, in case of lice. But don't fret, yours will be as long as mine in two or three years.'

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

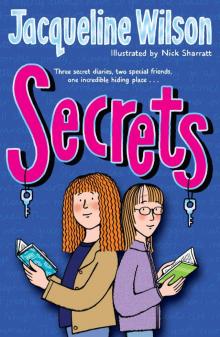

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets