- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

Rose Rivers Page 12

Rose Rivers Read online

Page 12

‘That’s so sweet of you, Rose, but I couldn’t possibly. I’m sure the teatime leftovers are pounced upon by the servants for their own tea,’ Miss Rayner said. ‘I wouldn’t want to deprive little Mary-Jane or Jack.’

I was surprised she knew their names.

‘Oh, we sometimes have little chats on the back stairs. I like children,’ said Miss Rayner.

‘Miss Rayner, don’t you think it strange that we Rivers children are nurtured and educated so carefully while Mary-Jane and Jack have to look after us and don’t have any education at all?’ I asked.

‘My goodness, Rose, you and your questions! It’s just the way of the world, dear. You were born into a rich family and Jack and Mary-Jane into poor ones.’

Looking at Miss Rayner’s patched dress and old worn boots, I realized that she was poor too.

‘I shall ask Papa if he can pay you a better wage so that you can have more treats – and a warm pair of gloves,’ I said.

‘That’s a very kind thought, Rose, but please don’t. I think I’m being paid ample already, especially as I no longer teach Rupert and Beth – and I’m clearly inadequate when it comes to giving you tuition.’

‘I think you’re doing a valiant job, Miss Rayner,’ I said, and resolved to be much nicer to her in future.

I went to ask Cook if she could bake a cake specially for Miss Rayner. She said she didn’t see why she should bake extra, her budget was tight enough already, and it wasn’t as if Miss Rayner was undernourished. She smiled nastily as she said this, and Maggie and Mary-Jane tittered.

Then I waited impatiently for Algie to return from the afternoon walk. The children had been out for a long time. Nurse was all in a fluster when she brought them back at last. Phoebe was crying because she needed a fresh napkin. Sebastian was crying because some horrid boys had sniggered at his long hair, calling him a girly-boy. Clarrie was limping, complaining that her boots were too tight. And Algie was soaking wet because he’d waded right into the pond to rescue his boat.

‘Dear Lordy, what a to-do! There there, baby, Nursie will change you in just a moment. Master Sebastian, don’t take on so, dear – they were just naughty rough boys and I dare say they call everyone names. Miss Clarrie, wait just a few seconds and I’ll take off your boots and rub those poor tootsies, but I must get Master Algie’s wet clothes off him or he’ll catch his death,’ said Nurse. ‘Look at him dripping all over the carpet!’

‘He’s a little drip himself,’ I said. ‘Don’t worry about Algie, Nurse. I’ll get his clothes off and find him some dry ones while you attend to the other children,’ I suggested.

I scooped him under my arm like a rolled-up rug and hauled him along the corridor before he could protest. When we were in the night nursery he started kicking, so I dropped him on his cot and then sat on top of him.

‘Kick me once more and I’ll slap you,’ I hissed. ‘I’m so cross with you! How dare you paint my precious Robinson Crusoe!’

‘I was trying to make it look nice for you! The pictures were so grey and boring,’ said Algie.

‘Well, you’ve absolutely ruined it. And what did you do with my picture?’

‘What do you mean, your picture? I haven’t seen any picture.’

‘Don’t play the innocent with me, Algie Rivers. What have you done with it?’

‘I haven’t done anything,’ he wailed. His teeth were starting to chatter.

I knew that he was fibbing – but I also knew that he was soaking wet and getting very cold.

‘Keep still while I take your clothes off,’ I commanded, unpeeling each of his garments until I was down to his drawers. Then I yanked those off too.

‘Stop it! Get off me! Let Nurse do it!’ Algie yelled, struggling to escape.

‘I’m doing it.’ I grabbed a towel. ‘Here, I have to get you dry. You really need a bath after being in that stinky pond, but it will take ages to get enough hot water.’ I started rubbing him vigorously.

‘Leave off! You’re too rough! You’re hurting!’ Algie protested.

‘Stop being such a baby,’ I said. I wasn’t really hurting him, but I didn’t feel like dabbing him gently.

I was all set for a serious interrogation, but I’m also a responsible sister. I had to get him dry first. It would be just like Algie to take a chill and die and then haunt me for the rest of my days. When at last he was warm and pink, I went to the children’s wardrobe. Algie jumped up on the bed and started leaping around, stark naked.

‘For goodness’ sake, Algie, stop it!’ I commanded.

‘I’m not Algie. I’m a Whirling Dervish!’ he said, spinning like a top.

‘Stop whirling, Mr Dervish, and get dressed,’ I said, bringing an armful of clothes with me and sitting him back on the bed. I’d thought of a devious plan.

I put a vest and some drawers on him so that he wouldn’t suspect anything too soon, and then I pulled Clarrie’s dress over his head and got all the buttons fastened down the back before he realized that anything was up.

‘This shirt feels most peculiar!’ he complained. ‘It’s all tight and itchy.’

‘That’s because it’s a dress,’ I said. ‘I’ve decided that you’re such a horrid little boy that I’m turning you into a girl.’

‘No! No, stop it! I can’t wear a dress!’ Algie shrieked. ‘I won’t, I won’t!’

Even as a baby Algie had hated wearing skirts. He couldn’t wait to be dressed as a proper boy. So now he grew frantic, trying to tear off the frock, but his pudgy little fingers couldn’t reach the buttons at the back. Thank goodness they were tightly sewn. ‘Get it off!’ he roared.

‘What’s the matter with Master Algie?’ Nurse called from the day nursery, busy with Phoebe.

‘Oh, he’s just being silly, Nurse,’ I said, my hand over Algie’s mouth. He did his best to bite my fingers but I hung on determinedly. I put my head close to his and whispered, ‘Now, you’re going to stay a little girl until you give me back my drawing!’

‘Haven’t got your silly drawing,’ Algie said indistinctly. ‘Who wants a drawing of stupid old Mr Walker anyway?’

‘So you have taken it. Where have you hidden it?’

‘I’ve forgotten,’ said Algie. He tried to get the frock off again.

‘Algie! I’ll tell Nurse,’ I said.

‘I’ll tell Nurse you’re being beastly. And I’ll tell her, you’ve got a silly pash on Mr Walker,’ said Algie. ‘I’ll tell her right now!’

‘And I’ll tell her you stole my precious drawing, and she’ll get very angry and she’ll tell Mama, and then she’ll have you whipped,’ I said.

This wasn’t likely at all. Nurse rarely told tales on us, partly because our behaviour might reflect badly on her. Mama was strict, but we would have had to do something truly dreadful to be whipped. And who was to do the whipping? Papa would refuse outright. He’d never so much as smacked us. Mr Hodgson might be willing, but he was very old and frail now. And surely I’d be the one in trouble for drawing Mr Walker in the first place.

Luckily Algie didn’t think of this. He just heard the word whip.

‘I won’t be whipped! I’ll grab the whip, and then I’ll whip you – lash, lash, lash,’ he said, cracking his imaginary whip.

I tried to grab him. Unfortunately I caught hold of his borrowed frock, and the silk ripped with a terrible sound, paralysing us both.

‘What was that?’ Nurse called sharply.

‘Nothing, Nurse!’ I called, wondering how on earth I was going to mend Clarrie’s dress when I was so terrible at needlework. But it was too late anyway.

Nurse came into the room with a wailing Phoebe on her hip. She saw Algie, red-faced in the torn frock, and smacked him hard across the backs of his legs.

Algie screamed his head off.

‘Now stop that shrieking, Master Algie, I barely touched you,’ said Nurse. ‘How dare you rip Miss Clarrie’s frock! It’s her best silk too – I doubt I’ll be able to mend it without a patch, and then it’ll

only be good enough for playing at home. What are you doing in Clarrie’s frock anyway? I won’t have such goings-on in my nursery. Master Sebastian’s bad enough without you starting too,’ Nurse scolded.

‘I haven’t started anything!’ Algie sobbed furiously. ‘It wasn’t my fault! It was Rose – she did it!’

‘Hush now! It’s bad enough getting into such mischief, but downright wicked to blame your poor sister,’ said Nurse.

It was glorious to get my own back on Algie, but when Nurse said that Algie had to go straight to bed without any tea, I decided I couldn’t let him suffer any longer.

‘Algie’s actually telling the truth, Nurse,’ I said. ‘I dressed him up for a joke and then I accidentally tore the frock. I’m so sorry.’

‘Miss Rose!’ she said, shocked.

She didn’t smack me about the legs – I’m too old for that sort of treatment now – but she gave me a severe telling-off and sent me to my room. I was the one to go without any tea, but I didn’t really care. In a couple of hours I would be dining with Mama and Papa, and I’d started to find the plain nursery tea a very dull meal.

Even so, missing tea would have been torture for Algie. He seemed impressed that I’d taken the blame. Half an hour later he sidled into my room with his hands behind his back. He found me sitting up on my bed, head bent, arms clasped round my knees.

‘You’re not crying, are you, Rose?’ he asked. ‘You can cheer up now. Look!’ From behind his back Algie produced my drawing of Mr Walker, flourishing it like a conjuror at a birthday party.

‘So where did you hide it?’ I asked, grabbing it.

‘I didn’t hide it! Absolutely not! You probably just left it somewhere or maybe Edie picked it up and tidied it away or perhaps Papa saw it and thought it was his,’ Algie suggested. ‘Or, I know, Alphonse could have mistaken it for the newspaper and run off with it in his mouth.’

‘Or perhaps a little pig flew in through an open window and seized my drawing and made off with it,’ I said.

‘Perhaps it did,’ said Algie happily. ‘Anyway, I’ve been searching and searching for it for you because I knew how upset you were, and then at long last I came across it and here it is.’

‘So where was it?’ I persisted.

‘I forget,’ said Algie.

I didn’t have the energy to persist. I smoothed out the crumples and put it back between the pages of Robinson Crusoe.

‘Mr Walker will get squashed in there,’ said Algie.

‘I’ll squash you if you’re not careful.’

‘You really do love him, don’t you?’

‘Of course I don’t,’ I said, feeling my cheeks grow hot.

‘You’ve gone all red!’

‘No I haven’t,’ I insisted.

‘Yes, you are in love with him, I can tell! That’s stupid, because you’re just a little girl still and he’s a man like Papa,’ said Algie.

‘If you go on like that I shall spread equally silly rumours about you, Algie. I’ll go round telling everyone that you’re in love with … Cook!’

‘I am in love with Cook,’ Algie declared. ‘Every afternoon I tell her I love her, and she gives me a slice of pie and lets me scrape the cake mix out of the bowl. When I’m big I’m going to marry her and she’ll make me jam roly-poly every day, even for breakfast, and we’ll live happily ever after, so there!’

It’s a waste of time trying to outwit Algie. And he’s right, isn’t he? I think I am in love with Mr Walker. I fizz all over at the thought of him, I daringly whisper his name, Paris, over and over again as if it were poetry, and I remember every word he says, every look he gives me, every gesture, every smile.

I’ve gone back to the daily portrait sessions. I knew that Mama would be annoyed – it’s obvious she wants Paris all to herself, but I can be as artful as Algie.

I went to see Papa first. I sighed and moped until he said, ‘What’s the matter, chickie?’

I ducked my head and acted shy, and then at last I burst out, ‘Oh, Papa, I wish I had your talent. My work is so stiff and clumsy compared with yours.’

He put his arms round me and told me that I was already a very promising little artist.

‘Of course, you haven’t quite got all the skills yet, darling. It will take years of practice before your pencil glides over the page. My goodness, it’s still a struggle for me, and I’ve been sketching for the last twenty years! Have you seen the number of times I tear out a page and chuck it at the wastepaper basket? My drawings of street children have been so challenging. I want to keep them simple and true to life, showing them in their sad rags and sordid surroundings, yet I also want to show their liveliness, their joy when they run around and play their funny games.

‘There’s one child who haunts me. I first came across her in the doll-maker’s shop, the one I mentioned. She looks like a little gypsy – she’s grubby and bashed and bruised, poor mite, and yet she’s the sparkiest of them all. She looks after all the children in her alley better than a mother, inventing so many fanciful games. She’s always burdened with a baby on her hip, but she joins in with enthusiasm. She runs faster than any of the boys, and gives a clout here and a kick there, but she’s so gentle with one little lad with withered legs, always letting him play too. It’s a joy to see her.’

‘I wish I could meet her, Papa,’ I said.

‘I’ve very nearly finished the drawings, but I tell you what, Rose, when they’re done we’ll start up our own special sketching sessions, you and me. We’ll wander all over London and select our subjects and draw all morning, and then we’ll come back to the studio and see if we can develop our rough sketches into something worthwhile. It will be good to have my studio back. I can’t seem to work there while Paris is painting his portrait of your mama. But you should watch him. He has great talent and you could learn so much. One day I’m sure he’ll paint a truly great portrait that will set the world on fire.’

‘Like your painting of Louisa in her black dress?’ I said.

Papa shook his head and didn’t reply. I’m sure Louisa was more than his muse. I think she was his sweetheart too. I feel so sorry for him.

I am sad for Papa but I’m so happy for me, resuming my so-called sketching sessions.

Needless to say, Mama is not at all pleased.

‘I thought you had got tired of drawing, Rose. You haven’t been making much progress, as far as I can see. Maybe you should run along back to the schoolroom.’

‘Papa wants me to persevere,’ I said.

‘And quite right too,’ said Paris. ‘I think we should encourage her, Mrs Rivers.’

‘Oh, well, if you think so, Mr Walker,’ said Mama, suddenly all smiles.

When she’s with him she acts in an embarrassingly girlish way. I wouldn’t have been surprised if she’d produced a fan and tapped him on the wrist with it.

We settled into the morning session, Mama posing in her blue dress, Paris painting her, and me sketching the pair of them, though my hand was shaky and I couldn’t draw properly. I watched Paris most of the time. His portrait is astonishing. Mama comes to peep at it whenever she needs to stand up and stretch.

‘I hope the portrait pleases you, Mrs Rivers,’ said Paris. ‘You make me feel anxious when you come and look at it.’

‘You need have no qualms on that score, Mr Walker. I am extremely pleased. It’s a remarkable likeness,’ said Mama complacently.

I hung around when she went to change out of the blue gown for lunch.

‘I’m glad you’ve come back,’ said Paris.

‘I’m glad too,’ I said. I looked at Mama’s portrait.

‘A remarkable likeness?’

We exchanged glances.

‘You’ve seen my work. Let me see yours.’ Paris reached for my sketchbook.

I was so ashamed of my childish scribble that I tore the page out, crumpled it into a ball and tossed it in the wastepaper basket.

‘Oh dear,’ said Paris. He bent over the basket to retrieve i

t.

‘Please don’t!’ I said. ‘It’s quite terrible, truly.’

‘Then show me a sketch you’re proud of.’

‘I’m not proud of any of them. Mama’s right, I’m not making any progress whatsoever,’ I said.

‘Show me!’

I stepped away so that he couldn’t see as I flicked through the pages of my sketchbook. I was so relieved that I’d torn out all the portraits of him. I chose one of Papa, blushing as I held it out.

‘You see? It’s no good, is it?’ I said.

I expected him to argue, and tell me I showed promise, like Papa. Instead he shook his head.

‘Do you want me to be truthful?’ he asked.

‘Yes please. Absolutely truthful. I shan’t mind a bit,’ I said.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘It’s good enough, quite competent, but it’s just a schoolgirl sketch.’

I knew this, but I found I minded after all.

‘I’m sorry. I think I’ve been too harsh,’ said Paris.

‘No, not at all,’ I said, my voice a bit wobbly.

‘I’m comparing your sketches with students’ work at the Academy, which is ridiculous of me. They’re really …’ He was obviously searching for the right word.

‘Promising?’ I said.

‘Yes!’

‘That’s what Papa says. With that exact intonation,’ I said, sighing. ‘I think Mama is right: I am wasting my time.’

‘Do you enjoy sketching, Rose?’

‘Not really.’

Not at all, actually. It’s so boring sticking to what I can see. I go tense and my hand gets tired and my neck aches from looking up and looking down. I don’t know how Paris and Papa can paint all day, working on the same little patch of canvas.

‘What do you like to do most then?’

‘Reading. Writing. Daydreaming! I do like drawing, but only my own comic nonsense.’

‘What sort of comic nonsense?’ Paris asked. ‘Show me.’

‘I just scribble silly stuff. Papa laughs at it but says it’s time for me to start doing serious work. Perhaps I’m simply not a serious person,’ I said.

‘Let’s see. Please.’

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

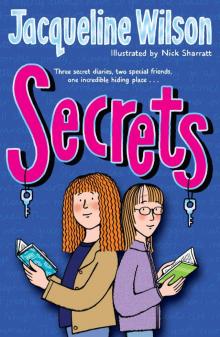

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets