- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

Lola Rose Page 2

Lola Rose Read online

Page 2

‘You can’t tell him!’

My stomach churned. Mum could be so stupid. I knew that look in her eyes. She was telling herself a little fairy tale. The footballer would clasp her to his six-pack chest and tell her he’d been picked to play for Manchester United and would she be his bride in the million-pound mansion that he’d just bought. Plus he’d take Kenny and me too. Mum drifted into Dreamworld and went shopping with Victoria Beckham every day while Kenny and I asked Brooklyn and Romeo round to play with all our new toys . . .

‘Mum!’ I wanted to shake her. I knew her footballer. He had a different girl every week. He’d never stick with Mum. And he wouldn’t want Kenny and me tagging along. Anyway, even if it all came true, even the Man U part, Mum couldn’t possibly live happily ever after. Dad would smash his way through the big picture window and tear the footballer’s head off his shoulders and then he’d beat her until the fluffy white carpets turned red.

I hated saying this to Mum but I had to make her see sense. Then Dad heard some rumour anyway and came straight back home. You could tell by the way he banged the front door that this was it. Big trouble.

He didn’t start straight away. He asked Mum questions, his voice very quiet, very soft. ‘Come on, Nikki, don’t look so scared. I just want you to tell me I’ve got it all wrong. If I have, then fine, I’ll drop it straight away. I’m a reasonable guy, aren’t I?’ Then, suddenly yelling, ‘Aren’t I?’

Mum panicked. She gabbled that he’d got it all wrong, she’d never so much as looked at another man, though of course she couldn’t help being lonely while Dad was away, but even so she’d never dream of talking to any other guy, let alone ask them in for a coffee . . .’ Any minute now she’d be letting it all out, telling him everything.

I wished I were as little as Kenny. He always hid under his bed, clamping his hands over his ears so he couldn’t hear. I had to listen, even though I couldn’t bear it.

Dad took much longer than usual. He said he was teaching her a lesson she’d never forget.

When he’d finished he stormed off out again. I ran to Mum. I wondered if I should call an ambulance. She couldn’t speak because her mouth was all bloody and swollen but she shook her head when she saw me pick up the phone. She’d been up to the hospital several times in the past. She never told on Dad, she always said she’d tripped or walked into a lamppost, but Dad got even madder if he found out.

I mopped her up as best I could, holding a cold flannel to her poor face. I cried all over her. I felt so bad that I hadn’t been able to protect her.

She couldn’t go out for a week because of the bruises. Not just on her face. I saw her in the bath. Her breasts and stomach were black.

I looked at my mum then and knew I hated my dad.

‘Don’t tell Dad about the lottery money,’ I begged Mum.

‘Don’t worry, I’m keeping quiet. Lips zipped, like I said.’

She asked for it in five-pound notes so it looked as impressive as possible.

‘We’re in the money!’ she sang, tossing handfuls of fivers in the air. They fluttered like big blue butterflies, sticking in her hair, catching on her clothes, landing all over the carpet.

‘Mum, stop it, you’ll lose some!’ I said, trying to gather them up.

‘You win some, you lose some,’ Mum laughed, tossing more.

Kenny laughed too, kicking his way through a pile of notes as if they were autumn leaves.

‘Leave off, Kenny,’ I said.

But I started to get carried away too, scooping the money up and then scattering it again. These crisp new notes didn’t seem real. I thought of the picture of the denim jacket lined with soft pink fur I’d cut out and stuck in my scrapbook. I knew if I could only own such a garment I might have a chance of looking as little and cute and blonde as the girl model.

‘What are you dreaming of buying, Jayni, eh?’ said Mum, putting her arm round me. She rubbed her soft cheek against mine.

‘Well, there’s this jacket—’ I started. Then I swallowed. ‘No, it’s your money, Mum. You already treated us in Sid’s.’

‘Don’t be so daft. What’s mine is yours. And yours too, Kenny. What do you want, my little pal?’ Mum asked.

‘A comic and a red ice lolly,’ said Kenny.

We groaned at him.

‘Something else, Kenny. Something big. Like a denim jacket with fur.’

‘I’d like a jacket like Dad’s. Leather!’ said Kenny, his eyes shining. ‘Then I’d look a big boy. Big and tough.’

‘You, big and tough, matie?’ I said, picking him up and blowing a raspberry on his tummy.

‘What about Dad?’ said Kenny, squealing. ‘What’s he getting?’

I looked at Mum. She sighed and started gathering up the money. I set Kenny down and started helping her.

‘We’re not telling Dad, Kenny,’ I said, smoothing the five-pound notes, assembling them into neat rectangles.

‘Why?’

I looked at Mum.

‘Why aren’t we telling him, Jayni?’ she said.

‘Because we know what he’s like. He could take it all for himself and waste it on some business deal that goes wrong. Or he could take it down the betting shop, or go away on a bender with his mates – and it’s your money, Mum.’

‘Yeah, but maybe it’s not fair, if we’re all having presents,’ said Mum. ‘Here, I could kid on I just won a bit, right, and then hide the rest.’

‘He’ll find out and then he’ll be furious. And then he’ll start.’

‘Yeah, OK,’ said Mum flatly. ‘Right. Well, we’ll be sensible. I’ll put the money in a building society and save it for a rainy day. And you won’t get your new jackets, kids, but we can’t make your dad suspicious – isn’t that right, Jayni?’

‘Yes,’ I said, putting the money in her bag.

I hated it that I had to be the one to be sensible. And I ached for that denim jacket.

‘Can’t I have my leather jacket like Dad’s?’ said Kenny.

‘No, love. Jayni says we can’t,’ said Mum.

It wasn’t fair. I hate the way Mum twists things sometimes. She tries to turn me into the mum. Then she blames me for spoiling things.

I threw the rest of the money at her and went off to my bedroom to work on my scrapbook. I started cutting up my new magazines, though Kenny had been at my scissors and they were all gummed up with sellotape. I picked all the mucky little sticky bits off the blades, my teeth clenched. Then I carefully cut out a Victorian doll with a purple crinoline. I snipped my way round every little twist and turn of her full frock and steered very slowly around her tiny button boots and cut in and out of her fiddly little fingers. I pretended I was a Victorian girl in a big purple dress and this was my matching doll. I had a little brother who was very obedient and adored his elder sister. We didn’t have a papa.

Then I cut out a tiny, toffee-brown cocker spaniel puppy with very floppy ears and a Siamese kitten with a delicate heart-shaped face and big blue eyes. These were our pets, Toffee and Bluebell. I cut some flowers from my birthday card box and a blue sky background and then I tried to draw a big Victorian house because I couldn’t find a proper picture of one anywhere. I’m not very good at drawing so I just did a rough outline of a big house. I cut out girls’ faces from Girltalk and stuck them looking out of all the windows, bordered by wax crayon purple velvet curtains. These were all my very best friends, Charlotte, Victoria, Emily, Evangeline and Jemima. It took me ages to think up special Victorian names.

I was so lost in my scrapbook world that I didn’t hear the front door bang. I didn’t know my dad was home until I heard him call, ‘Where’s my princess then?’

I shut my scrapbook up quick and shot into the living room. It’s never a good idea to keep my dad waiting. But he’d called me princess, which was a promising sign. He might be in a good mood.

He smiled as I rushed into the room. ‘There’s my girl!’ he said, beckoning me over to his armchair. Kenny was already on his knee

. Mum was snapping open a can of beer and pouring it for him.

‘Great, isn’t it, Dad’s home early,’ she said.

I breathed in. ‘Hi, Daddy,’ I said in this false small-girly voice.

‘Hi, Princess,’ Dad said, and he patted the arm of his chair.

I perched there obediently. I stretched a smile across my face while my eyes swivelled all round the room, looking for a forgotten fiver on the rug, under the coffee table, tucked in the telly mags. I couldn’t see any but I still couldn’t breathe out comfortably. Dad was in a good mood, but he could turn in seconds. You never knew what might set him off. Some silly little thing you said – sometimes just a look, sometimes it seemed like no reason at all. It was as if Dad’s head was wired up weirdly and every so often he was programmed to explode.

But today he seemed mellow, even though he said he’d had a row at work so he’d walked out. ‘And about time too. Who wants their poxy job?’ he said.

Three months ago, when he’d started working there, he’d had us all reciting that it was the best job ever, his Fresh Start.

He was making another Fresh Start now. He’d met an old mate down the pub at lunch time who was setting up his own minicab firm. He wanted Dad to join his team of drivers.

‘Will he provide the car, like?’ Mum asked.

‘No, I’ve got to get the wheels, babe.’

Mum always softened when Dad called her babe. She forgot that he could also call her a dozy cow or worse.

‘Still, that shouldn’t present too many problems. There’s a mate of mine wants rid of a very nice little Escort, two years old, not much mileage to speak of. He’ll let me have it dirt cheap too. I’ve just got to raise a few thousand. I’ll get a loan off someone, just you wait and see, babe. My luck’s changed. I can feel it.’ He reached out and patted Mum on her bum.

‘Jay!’ She laughed at him – and I felt my stomach screw up in a knot. She was looking at him like he’d suddenly turned into a handsome prince. ‘It is our lucky day,’ she said.

She was going to blow it. She was going to tell him.

Don’t! I mouthed at her. She just blinked at me, pretending she hadn’t seen.

‘You’ll never ever guess what, Jay,’ she said. She went to her handbag and fanned out a great handful of fivers. ‘Here’s your car money, darling. I won it on a scratch card! There’ll be enough for treats for all of us. Our Kenny wants a little leather jacket just like his dad. Jayni wants one of them denim jackets lined with fur – pink fur, isn’t that right, pet?’

I had to smile and say yes and act all excited.

I was scared it was going to go horribly wrong. Dad paused, staring at the money in Mum’s handbag. You could see his brain going tick, tick, tick. But then he threw Kenny right up in the air and caught him and whirled him round. He pulled me up too and we danced round and round and then he danced with Mum, giving her a great big movie-star kiss, telling her she was his Lady Luck.

We went out for our tea to T.G.I. Friday’s to celebrate. Mum and Dad had fancy cocktails and then we ordered this h-u-g-e meal. I started to wonder if it was going to be all right after all. Dad was larking about and cracking jokes and flirting with the waitress. I wanted to believe in fairy tales and have fun too. I ate all my giant burger and chips and then an entire Death by Chocolate.

These women on an office outing came over to Dad, as giggly as girls, and asked if he was Jay Fenton who used to sing with the Mad Beggars. When Dad said he was they all squealed. The prettiest one with the lowest-cut top stuck her head up close and asked if he’d give them a little song now. They were having a great night out but this would be the icing on the cake.

‘I’ll be the cherry on top of the icing, darling,’ said Dad, and he went over to their table and sang to them all.

Mum drained her glass of wine and then ordered another bottle. ‘What?’ she snapped when she saw me looking at her. ‘Those women are buying your dad drinks, look.’

I didn’t want to look. I hated it when Mum and Dad drank lots because it always ended up in a fight. I buried my head in the menu instead, though I was so full up I had to undo the top button of my jeans. I read each meal description very carefully. I wished I could cut out some of the pictures for my scrapbook.

I used to play this game with Kenny – I’d find a picture in a magazine of a big chocolate cake with layers of thick cream and I’d reach out my finger and touch the paper cake and pretend to lick the cream off my finger, going, ‘Yum yum yum’. Sometimes it seemed like I could taste the cake, feel the smooth cream and the sponge crumbs on my tongue.

Kenny would beg me for a piece of cake. I’d hold the page out to him. He’d stab his fingers all over the slippery paper, trying to reach through into the soft cake. He’d suck hard at his fingers but he could never imagine it for himself. ‘I want the cake!’ he’d wail.

‘God, you’re not still hungry?’ Mum said, pouring the new bottle of wine.

‘God, you’re not still thirsty?’ I said.

‘Don’t you go all snippy with me, miss,’ said Mum, giving me a kick under the table. She was wearing her best black high heels with very pointy toes.

‘That hurt, Mum!’

‘Rubbish,’ said Mum, but she reached under the table and rubbed my shin. ‘There, that better?’ She was leaning so far forward she overbalanced and ended up under the table.

‘Whoops!’ She tried to get up and banged her head. She started half laughing, half crying.

‘Mum!’ I hissed, trying to hook her out.

‘Mum!’ said Kenny, giggling, thinking it was a big joke. He slid off his chair and squatted beside her, going, ‘Shh!’ as if it were a game of hide and seek.

‘Oh please, get up, Kenny. Mum, Dad will see. Quick!’

She couldn’t be quick to save her life. She just crouched there, clutching Kenny, tickling him now. Dad was looking our way. I gave him a sickly grin, waving like everything was all right. Dad stopped singing and came over to us.

‘What the hell . . .?’

‘Kenny fell under the table. Mum’s just trying to pick him up,’ I gabbled.

‘Dad! Dad, we’re hiding!’ Kenny squealed.

‘Well, now I’ve found you, and you’re coming up out of there, my lad,’ said Dad. He seized him under the arms and pulled. Kenny came up laughing and kicking.

‘Mind your drink, Kenny!’ I said, grabbing it just in time.

‘What about my drink?’ Mum said, trying to crawl out on her hands and knees.

‘What are you playing at, Nikki? Are you drunk?’ said Dad.

‘No – but what a good idea! Let’s all get drunk to celebrate. I’m Lady Luck, that’s what I am,’ Mum said, hauling herself up. Her hair was all tousled and her mascara was smudged.

‘You look a right mess,’ said Dad. ‘Come on, let’s go home. Jump to it.’

We jumped. I was scared all the way home, wondering what was coming. There was this awful Voice of Doom in my head. He’s going to beat her up.

Maybe Mum could hear the voice too. She started singing to shut it up, all her favourite old pop songs. Then Kenny started whimpering and Mum picked him up, balancing him on her hip, singing ‘Mr Sandman’. She used to sing it to me when I was little, very softly, very slowly, and whenever she came to the ‘lend me your ear’ bit she’d nuzzle it, pretending she was going to nibble it right off. It always soothed me and made me go to sleep. But Mum’s voice was too high and wobbly now. Dad didn’t join in the singing. He didn’t say a word all the way home.

The first thing he did when he got in was pour himself a large glass of whisky. He drank it back like tap water.

‘Right! Here we are. Our happy little family. Lucky us, won the lottery. Only it just suddenly occurs to me, Nikki, you’ve been acting a bit odd about all this. Why didn’t you tell me right away, eh? Why didn’t you yell it out the minute I got in? Were you going to keep it a secret? Were you going to keep quiet about the cash, keep it all for yourself, eh? Or maybe you we

re going to spend it on lover boy? Your little footballing chum. Still in touch, are we?’

‘Of course not, Jay. You’re the only guy for me, you know that,’ Mum said. She was still clutching Kenny. ‘Look, let me tuck Kenny up, OK? And you get to bed too, Jayni.’

‘Oh yes, to give you time to make up a few excuses,’ said Dad. ‘I wouldn’t bother, Nikki. I’ll get the truth out of you one way or another.’

Mum carried Kenny out of the room. She called to me to come too.

‘Are you deaf, Jayni?’ said Dad. ‘Get to bed.’

I wanted to go to bed and pull the covers right up over my head. But I didn’t go. ‘I’m staying up, Dad,’ I said.

‘You what?’ said Dad. Nobody ever spoke back to him. Especially not me.

‘You heard me, Dad,’ I said. My mouth was so dry the words were whispers. My chocolate pudding stirred round and round in my stomach.

‘Get to bed this instant, you cheeky little cow,’ said Dad. He got out of his chair and raised his hand.

I wanted to be brave but I couldn’t help squealing then. I didn’t make much noise but Mum came running. She saw us, Dad’s hand in the air, me ducking, like we were both stuck playing a grim game of statues.

‘Get to bed, Jayni!’ Mum said.

‘I’m staying here,’ I cried.

‘What’s got into you?’ Dad said.

‘It’s you! You spoil everything! Even a lovely thing like Mum winning the lottery. It’s all spoilt because of you and your moods and your shouting and your hitting. I knew you’d be like this. Why can’t you be like a real dad?’ I yelled.

Dad’s head jerked as if I’d hit him. He stood still, shaking his head, as if he couldn’t quite work it out. I think that’s why he hit me. He didn’t know what else to do.

It was a slap across my face that lifted me right off my feet. I ended up flat on my back on the carpet. Mum leapt at Dad, scratching his face with her long nails. He punched her and then when she was on the ground beside me he kicked her. Then he spat at both of us and walked out. The door slammed behind him.

‘Oh, Jayni, let’s look at you,’ said Mum, kneeling beside me.

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

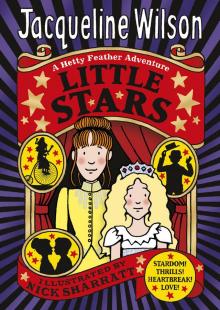

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

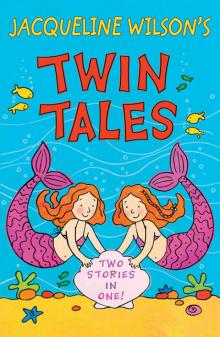

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets