- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

Glubbslyme Page 3

Glubbslyme Read online

Page 3

‘That smell!’

‘Yes, it always smells a bit round here in the summer,’ Rebecca apologised.

‘That beauteous dank aroma is unmistakable!’ said Glubbslyme. ‘We are by the brook. My dear Rebecca dwelt beside the brook. I will see my own home!’

He hopped up and down inside the carrier in his eagerness. Rebecca was scared he might hop right out, so she pierced his carrier with her hair slide, making him two little peepholes. Glubbslyme peeped and peeped, but to no avail.

‘I think it’s all changed now,’ said Rebecca. ‘There aren’t really any houses down this road. There’s just the shops and the Old Oak, that’s the pub on the corner.’

‘A fine young oak spread its boughs over our very cottage. My Rebecca used its oak-apples in many a magic potion,’ said Glubbslyme, abandoning his peepholes and peering round eagerly out of the top of the carrier bag. ‘But where is the oak tree now?’

They walked along to the end of the road. There wasn’t so much as an acorn.

‘I think they must have chopped it down,’ said Rebecca. ‘And now they’ve built the pub in its place.’

‘Dastardly rogues!’ croaked Glubbslyme. ‘Then they have also chopped down the dear old cottage. Oh woe! Oh misery and anguish! I did so desire to visit it once more. I wished to erect another memorial tablet in honour of my dearest Rebecca.’

He glared at the public house, eyes brimming with emotion. And then he blinked. His great gummy mouth smiled. He puffed up with pride, almost filling the carrier bag.

‘They have erected their own memorial tablet to the wise and wicked Rebecca Cockgoldde,’ he said, and he pointed to the Courage brewery’s pub sign. It was a golden cockerel.

Rebecca unlocked her front door and carried Glubbslyme over the threshold.

‘Well. This is my house,’ she said.

She laid the carrier bag gently on the hall carpet. Glubbslyme sat motionless, lurking under the plastic.

‘Glubbslyme, are you all right?’ said Rebecca anxiously, peering in at him.

‘I doubt it,’ said Glubbslyme weakly. ‘The whole world is swinging backwards and forwards, backwards and forwards.’ He hopped unsteadily out of the carrier, reeled down the carpet, and then froze by the stairs.

‘Pick me up!’ he commanded in a high-pitched croak. ‘Pick me up immediately!’

‘What’s the matter?’ said Rebecca, obediently lifting him.

It was strange how quickly she’d got used to handling him. She didn’t really mind the feel of him at all. In fact she wouldn’t have minded petting him properly, but didn’t dare try in case Glubbslyme thought it a liberty.

‘You said you were not allowed to keep pet animals,’ Glubbslyme hissed from her cupped hands.

‘I’m not.’

‘Is the bear cub prowling on the staircase not an animal – and exceeding dangerous?’

Rebecca burst out laughing.

‘That’s Shabby Bear. My old teddy. He’s a toy, Glubbslyme, he’s not real. I always used to sit with him on the stairs when I was little, and now I keep him on the stairs most of the time.’

Rebecca felt she was far too old for teddy bears, but when she had to come home to an empty house she liked to have Shabby there, waiting, ready for a cuddle if necessary.

Glubbslyme did not seem to understand. Rebecca abandoned her explanation and politely offered to show him round the house. She carried him into the living room. Glubbslyme blinked a lot. She thought he might be impressed by the television so she switched it on. It was ‘Blue Peter’ but Glubbslyme reacted as if it was ‘Driller Killer’. He hopped several feet in the air and landed inelegantly on his bottom, his legs waving.

‘What occult trick is this?’ he cried.

‘It’s only television, Glubbslyme. It’s not frightening, honestly. Look, I’ll swop channels if you like.’

Glubbslyme did not care for any of the channels. He croaked in terror at them all so Rebecca switched the television off. Glubbslyme lay on the furry rug, recovering. Then he sat up and flexed his feet several times.

‘Remove me from this dead sheep, if you please.’

Rebecca put him on the best armchair instead but it was Dralon, and it tickled him even more. He scratched. He shuddered. He sighed.

‘How about a little paddle to soothe your skin?’ Rebecca suggested imaginatively. ‘Come with me.’

She took him upstairs. Glubbslyme cowered as they passed silly old Shabby, mumbling about a performing bear that had once broken free from its chain and given his Rebecca a savage bite.

‘Well Shabby can’t bite you, Glubbslyme, he hasn’t got any teeth,’ said Rebecca.

She took him up to the bathroom. It was a very poky little room and Rebecca and her Dad didn’t always remember to clean round the bath or wipe the toothpaste stains off the basin, but Rebecca suspected that it would still seem luxurious by seventeenth century standards.

Glubbslyme wriggled free and scrabbled about the shabby floor tiles, exploring. He discovered an old plastic duck in a corner, left over from when Rebecca was a baby. He hopped around it, obviously puzzled by the shiny yellow plastic. He stuck out a leg and kicked it. The duck rocked crazily and fell on its beak.

‘It is dead,’ said Glubbslyme. ‘You seem inordinately fond of dead animals, Rebecca. Dead sheep, dead bears, dead water fowl.’

Glubbslyme was very much alive. He was fascinated when Rebecca filled the basin and bath for him. He had a hot soak in the washbasin and then jumped into the cold bath and had an invigorating swim. He floated the flannels as if they were water lilies but spurned the soap after one suspicious sniff.

He could not understand how the clean cold water and the piping hot were conjured at the mere turn of a tap.

‘It is sorcery of the highest sophistication,’ he said, sounding awed.

‘But it doesn’t scare you like the television?’

‘How could I be scared in my own element?’ said Glubbslyme. He jumped up onto the side of the bath and peered round at the lavatory. ‘I think I shall try the little pool now,’ he said, poised for a jump.

‘No! It’s not a pool,’ said Rebecca, hurriedly putting the lid down. ‘You can’t go paddling in there, Glubbslyme.’

‘Why? What is the purpose of the little pool?’

‘Well. It’s a loo. You know.’

Glubbslyme obviously didn’t so she had to explain, going rather red in the face.

‘A privy!’ said Glubbslyme. ‘A privy inside the house!’ He sounded astonished at such an idea.

Rebecca flushed the chain to show him how it worked and talked rather vaguely about cisterns and sewers. Glubbslyme asked intelligent questions that she couldn’t always answer.

‘I’ll get my Dad to tell you,’ said Rebecca. ‘Oh I can’t wait until you meet each other. I can’t wait until he hears you talk! I can’t wait!’

‘You will have to wait,’ said Glubbslyme. He sidled along the edge of the bath, looking serious. ‘I will not be talking to your father.’

‘What do you mean? Oh Glubbslyme, he’s ever so nice, really he is, you’ll really like him.’

‘I dare say, but that is not the point,’ said Glubbslyme. ‘The point is this: I may be a familiar but I am not familiar with all and sundry. I am only familiar with one chosen fortunate.’

‘But he’s my Dad. He’s my family.’

‘I am not even familiar with family.’

‘Oh please, Glubbslyme. Just talk to my Dad. Look, he’ll be home any minute. Oh dear, I should have started tea, I did promise. Still never mind, when he meets you he’ll forget to be cross. Oh Glubbslyme, please, please, do talk to my Dad. You needn’t say very much if you feel shy.’

‘I never feel shy,’ said Glubbslyme indignantly. ‘And I never talk to strangers.’

‘But he’s not a stranger, he’s my Dad.’

‘He is strange to me. You are the only person with whom I am intimate,’ Glubbslyme insisted.

Rebecca couldn’t

help feeling a little warm pride in spite of her disappointment.

‘Just one little croaky How do you do?’ she suggested, not willing to give up altogether.

‘I do not think you understand plain English,’ said Glubbslyme irritably.

He jumped into the bath, deliberately splashing her. Glubbslyme’s English seemed very fancy indeed to Rebecca, but she knew what he meant.

‘All right then,’ she said, wiping her eye. ‘Only it’s going to be so difficult getting him to believe you can really talk if you won’t do it for him.’

‘You will not tell him anything,’ said Glubbslyme, jumping out of the water and glaring at her. ‘If you talk about my magical powers they will immediately decline.’

‘Can’t I even tell him you were Rebecca Cockgoldde’s familiar back in the seventeenth century?’

‘Indeed you cannot.’

‘I think that’s very mean,’ said Rebecca, and she flicked her fingers and thumb in the water and splashed Glubbslyme back. It was only a little flick, a little splash, but Glubbslyme swelled. He leapt in the air and then hurtled down into the full bath, his arms and legs tucked into his body. Rebecca did not get splashed. She got soaked.

‘You beast!’ she said. She splashed at him wildly but he just bobbed up and down in the water, laughing. Then he jumped right up and splashed her again. She tried to duck but she wasn’t quick enough. Her dress was now as wet as it had been when she fell in the pond.

‘Will you stop it!’ she shrieked. ‘Look at me! Look at the floor, there’s water slopping everywhere. And my dress! How am I going to get it dry before Dad gets home, eh? You can’t make the sun shine right through the ceiling.’

‘I can do anything,’ said Glubbslyme. ‘I am the Great Glubbslyme, once the familiar of the wise and wicked witch Rebecca Cockgoldde, now the familiar of the small and very silly Rebecca Brown.’

‘I wish you’d stop insulting me. You haven’t half got a cheek,’ said Rebecca.

She splashed him again and he croaked mockingly. She reached out and seized the bottle of bubble bath. She shook it and then squeezed hard. A stream of bubbles spurted over Glubbslyme. He flailed wildly through the scented froth, spluttering.

‘Oh Glubbslyme, you do look sweet,’ said Rebecca, giggling wildly.

‘You wanton little maid!’ Glubbslyme croaked, bubbles foaming from his mouth. ‘Rinse this foul scented brew from my person immediately!’ He tried to turn on the bath taps himself but his little fingers weren’t quite strong enough.

‘Aha, you need my help now, don’t you,’ said Rebecca triumphantly. She leant over to help him but as soon as she’d turned the cold tap full on Glubbslyme stuck his fist in the flow so that the water shot right up into Rebecca’s face.

‘There! That will teach you to play tricks on me,’ he said, sluicing the foam off himself.

‘You horrid little toad!’ Rebecca shouted, reaching for a dry towel. They all seemed to be very wet now. ‘And I was trying to help you too!’

‘You will soon learn that you will never get the better of the Great Glubbslyme. I can manipulate water in all manner of ways. Cease your silly little tricks lest I evoke all my magical powers.’

‘I’ve got my modern magic too, don’t forget,’ said Rebecca, giving him a little poke with her toothbrush. ‘I could always grab hold of you and throw you down the loo and pull the chain, so there!’

Glubbslyme puffed into a football, his eyes revolving.

‘Beware lest I conjure a wart on the end of your nose – or worse!’ he threatened.

‘You wouldn’t dare,’ said Rebecca foolishly.

Glubbslyme jumped up and rubbed her nose hard with one of his fingers. Rebecca gasped. She could feel something soft and strange on her nose. She could see something large and pink when she crossed her eyes. She gave a little shriek and ran to the bathroom mirror. A wart!

‘Oh no!’ she wailed. And then the wart fell off into the washbasin. She looked at it properly. It wasn’t a wart at all. It was a piece of her own pink soap.

Glubbslyme shrieked with laughter, lying back in the bath water and kicking his heels.

‘Fooled!’ he chortled joyfully.

‘You wicked little tease,’ said Rebecca. ‘I’m really going to get you now.’

She reached for the bubble bath again. Bubbles blew up all round them. Glubbslyme splashed. Rebecca squirted. They both shrieked.

And then the front door slammed downstairs.

‘Rebecca, I’m home.’

‘It’s Dad!’ Rebecca gasped.

Rebecca looked at Glubbslyme. She looked at the brimming bath, the sprayed walls, the sodden carpet, her soaking dress.

‘You can’t magic everything dry, can you?’ she asked urgently.

Glubbslyme blinked at her and did nothing.

‘Rebecca?’ Dad called. ‘Rebecca, where are you?’

‘I’m coming, Dad,’ Rebecca shouted, swooping round the bathroom with one of the towels.

‘Oh Becky, honestly, you haven’t even put the oven on,’ Dad’s voice grumbled from the kitchen. ‘Don’t you remember I told you to? Here, what’s happened up there? There’s water dripping through the kitchen ceiling.’

‘Oh help!’ Rebecca whispered.

Her own eyes popped like Glubbslyme’s in her panic. She unplugged the bath water and Glubbslyme started wafting up and down on the waves. She heard Dad’s footsteps hurrying up the stairs.

‘Oh no! Glubbslyme, help me.’

Glubbslyme didn’t. Dad banged on the bathroom door.

‘Rebecca? What are you doing? Did you leave the tap running?’

‘Yes, sorry Dad, but it’s all right now. I’ll be out in a minute. You go away now,’ Rebecca gabbled.

Dad didn’t go away. He opened the bathroom door and came right in.

‘Oh my goodness, what are you up to now?’ he said, his hands on his hips. ‘Look at you. What have you been trying to do? Swim fully-clothed in the bath?’

‘No Dad,’ said Rebecca miserably.

‘And look at all these bubbles! You’ve wasted half the bottle, you naughty girl. Really Rebecca, you’re not a baby any more, you’re too old for these silly games, and – WHAT ON EARTH IS THAT?’

Dad had suddenly noticed Glubbslyme, who was revolving round and round the bath plug as the water ebbed away.

Rebecca took a deep breath.

‘It’s my pet toad, Dad.’

‘Your what?’

‘It’s my toad, Dad. I found him in the pond in the park. Isn’t he lovely? I bet you’ve never seen such a . . . such a distinguished toad.’

Glubbslyme stopped whirling. He hopped up on the edge of the bath and bowed his warty head.

‘Ugh!’ said Dad, taking a step backwards. ‘Get it out of here!’

‘Okay Dad. He can sleep in my bedroom – and I swear I won’t forget to feed him – and I won’t make this sort of mess again, I promise, I just wanted to give him a swim and it got sort of wet—’

‘Rebecca, I think you’ve gone completely mad. I want you to take that toad out of here. Out of the house. I can’t understand why you aren’t scared to death of it. You had hysterics over a worm on your wellington boot only the other day.’

‘He isn’t a worm, Dad, he’s a toad.’

‘I can see that. And you can’t keep him, so stop talking such nonsense. Now go and get a box and we’ll try to catch him and then you’d better take him right down to the bottom of the garden and let him go.’

‘Dad, I can’t. He’s mine.’

‘Stop arguing! Come on, do as you’re told, get a box. And then you’d better help me clear up this mess. The water will seep right through to the electrics if we’re not careful.’

‘I’ll take him back to the park then,’ Rebecca said mournfully.

‘Of course you can’t take him all the way back to the park at this time.’

‘But I have to, Dad.’

‘Rebecca, the park will be closed. The gates will be lo

cked.’

‘I could climb over.’

‘Now you’re just being silly. I’m trying very hard indeed to keep my temper, Rebecca. Take the toad out into the garden AT ONCE.’

Rebecca knew she would never win when Dad used that tone. Tears started trickling down her cheeks. Dad saw them and sighed.

‘Come on, there’s no need to act as if it’s the end of the world. It’s the only sensible thing to do, love. No one keeps toads as pets. He wouldn’t be happy. He wants to be back outside so he can hop about in the grass and catch a few flies for his supper. Take him right behind the greenhouse, he’ll be happy there. Now get a box and we’ll trap him in it.’

‘I don’t need a box,’ Rebecca sniffed, and she held out her hands.

Glubbslyme hopped into them. Rebecca cuddled him against her damp chest. Dad looked amazed.

‘You see how tame he is,’ said Rebecca. ‘Oh please. If you only knew what sort of a toad he is—’

Glubbslyme stiffened in alarm. Perhaps it was just as well Dad did not want to know.

‘Out into the garden. Now.’

So Rebecca carried Glubbslyme out of the bathroom, down the stairs, through the kitchen and out into the garden. She whispered tearful apologies all the way. Glubbslyme didn’t reply until they were in the garden.

‘Watch that tongue of yours, child. Not a word about my powers, if you please. And pray staunch those tears. They are tickling.’

‘I can’t help crying, Glubbslyme. I’m so miserable,’ said Rebecca.

They had only known each other a few hours and yet she felt Glubbslyme was her greatest friend.

‘I’m going to miss you so,’ she said, sobbing.

‘You are becoming exceeding waterlogged,’ said Glubbslyme. ‘Mop those eyes. There is no call for grief. I shall bide overnight in the little dwelling yonder. Is it another privy?’

‘It’s the greenhouse!’

‘It is not green. It is I believe a white house, though dingy enough to mistake for grey. But green, grey or white, it will suffice,’ said Glubbslyme.

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

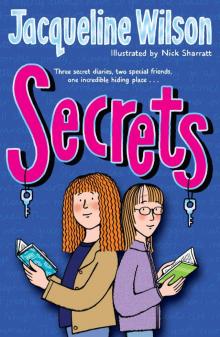

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets