- Home

- Jacqueline Wilson

Hetty Feather Page 4

Hetty Feather Read online

Page 4

I was lost in the horror of losing Saul. I would never ever have the chance to be a good sister to him. I screamed until my throat was raw. I went on screaming until I slept. When I woke, I had no idea whether it was morning or afternoon. The house was horribly silent, though I could hear a little snuffling noise close by.

I reached out across the bed, but there was no one there. The snuffling continued, from under the bed. I leaned out, hung my head down, and saw Gideon curled up beneath me.

'Oh, Gid,' I croaked, barely able to talk. 'Come up into the bed.'

But he wouldn't, so I crawled underneath beside him, lying on the cold dusty floorboards.

'What are you doing, Gideon?' I asked. 'Are you pretending to be a chamber pot?'

I said it to make him laugh but he went on snuffling.

'You cry ever so quietly,' I observed. 'I scream and scream.'

'I know,' said Gideon thickly.

His face was so sodden with tears and snot he could scarcely breathe. I very kindly lifted up my nightgown hem and mopped him dry.

'Is Mother back?' I asked.

'Yes. But Saul isn't,' Gideon whispered.

I swallowed. My throat hurt so much I held it on the outside, clasping my neck with both hands. 'I was a bad sister to him,' I said wretchedly. I wriggled nearer to Gideon. 'I shall be a lovely sister to you now, Gid,' I said, putting my arms round him.

I was smaller than him, but he felt very little and spindly in my arms. I could feel him trembling.

'Hetty, will Mother take us to this hospital?'

'Hush!' I said sharply. It felt so much worse to have Gideon put it into words. I shook him a little and then felt bad. Hadn't I only just that minute promised to be a good sister?

'Of course Mother won't take us,' I said as firmly as I could. I patted Gideon encouragingly. 'You are her favourite. She wouldn't ever take you. And Jem wouldn't let her take me. Mother won't take us. Never never never. Say it, Gideon. Never.'

'Never never never,' we chanted.

I thought I would ask Mother, just to be certain sure, but somehow the words dried in my sore throat when I saw her. She was grey with grief, clutching little Eliza to her bosom, tears rolling down her cheeks.

I asked Jem instead.

'You won't let me go to that hospital, will you, Jem?'

'No, Hetty,' said Jem, hugging me tight.

I looked up at his face. His eyes were very red.

'Have you been crying, Jem?' I asked.

Jem never cried. He didn't even cry the day one of the horses bolted and knocked him to the ground. He got kicked in the head, so that one side of his poor face was black with bruises for weeks.

'I'm staying here for ever and ever, aren't I, Jem?' I said again. 'And Gideon is too.'

'Yes, Hetty. Of course you are,' Jem said again and again, but he still didn't seem quite sure enough.

I couldn't get to sleep that night, and when I eventually dozed off I dreamed of Saul. A large cruel nurse was picking him up and plunging him into the water butt, trying to drown him like a newborn kitten. I screamed at her and she seized me too, holding me fast by the scruff of the neck. I struggled in the butt and her hand pushed me down, down, down in the murky water. I woke with a start and found there was murky water in my own bed too.

I thought Mother would be cross with me for being such a baby, but she scarcely said a word. She moved slowly about the house, her head bowed. She fed and changed Eliza, and cooked bacon and cabbage for all of us, but most of the time she sat staring at the floor, wringing her big red hands.

Rosie ushered us out of the cottage to give Mother some peace. We were huddled miserably on the doorstep when Father came striding home.

'Hello, chickens.' He ruffled our heads and sighed. 'Oh dear. No cheeps from any of you,' he said, stepping over us with his great legs.

He said no more until he'd eaten his supper. Then he lit his pipe and called us to come and stand by his chair.

'Nat, go down to the Otter Inn and fetch me a tankard of ale. No spilling a drop, do you hear? Jem, you go with him. Eliza, go and see to your namesake sister. See if you can quieten her grizzling. Rosie, take Mother upstairs – she needs to lie down. Be off, all of you. I want to have a word with Hetty and Gideon.'

When they were all gone, he shook his head at us. 'Such long faces! Are you missing young Saul?'

'Most dreadfully, Father,' I said.

He blinked at me. 'Why, Hetty, you do surprise me,' he said. 'You two were always fighting! No doubt you're full of remorse now?'

I nodded. I wasn't yet sure what remorse meant, but the cold, sour, sick feeling in my stomach seemed to sum it up.

'Poor child,' said Father, patting me.

I climbed up onto his great lap and nuzzled my face against his chest. I could hear his heart going thump against my cheek.

'Mother won't take me away, will she, Father?' I said into the rough cotton of his smock. 'Nor Gideon?'

I waited. I felt Father take several deep breaths.

'Not till next year, my sweetheart, when you are both much bigger.'

'No! No, not then, not ever!' I shrieked, pummelling him with my fists.

'Stop that now, missy!' said Father, catching both my flailing hands in his large one. 'You've shrieked enough today, I'm told. There's no point wailing when it can't be helped. Now hush and listen. Mother and I love you, love Gideon, love little Eliza just like our own children. We still love Saul—'

'And Martha,' I said.

'And Martha,' said Father, seeming surprised I'd remembered her. 'But you're not our children, you're little waifs from the Foundling Hospital. You came to us as tiny babies. Mother has a knack with specially frail babies. She rears you up until you're fat and rosy-cheeked.' He gently poked me in the cheeks with his thumb and finger, but I wriggled free, a new thought having struck me.

I was remembering the pig out in the back yard. Mother had a piglet every year, pale and puny. She fed it and fattened it until it could barely sway on its trotters, and then Father came along, and although we weren't supposed to watch, we heard squeal- squeal-squeal, and the next day there was fresh pork on our plates.

'Is she fattening us up to eat us?' I said, gazing at Father as if he was an ogre.

He stared back at me, slack-mouthed, and then he roared with laughter. 'Oh, Hetty, Hetty, you're a funny one,' he chortled. 'Of course no one's going to eat you! Mother will take you back to the Foundling Hospital when you're big enough, and you'll live with lots and lots of other girls. Martha will be there so you'll have one sister. And you'll be with the boys, Gideon, and Saul will be your brother.'

'I want to be with Hetty,' said Gideon, but Father paid him no heed.

'We need to be with you, Father. And Mother. And my Jem,' I said. 'Please can't we stay? I promise I'll be very, very, very good. I'll never shout or kick or cry ever again.'

'You're a caution, Hetty,' said Father. 'We would love you to stay here with us. We'd like to keep all our dear foster children, but you do not belong to us. You belong to the hospital. All foundlings must be returned by their sixth birthday. Don't look so worried. I'm sure they will be kind to you as long as you are a sensible girl, Hetty. They will school you properly and teach you to be a good Christian child.'

'Will we live there for ever?'

'No, no, they will train you up to be a servant girl and you will go away into service when you are fourteen,' said Father.

'Like Bess and Nora?' I said.

'Just like our Bess and Nora,' said Father. 'And then I dare say you can come home to us once a year just as they do.'

I pondered. Last Mothering Sunday I had admired my big sisters in their fancy print dresses and fine stockings when they'd travelled home on a visit. But they'd told Mother tales of cross cooks who beat them over the head with ladles and sly masters who tried to sneak kisses.

'I do not want to be a servant girl,' I said.

'Will I be a servant girl?' asked Gideon.

'Don't be dim-witted, lad!' said Father. 'No, no, I dare say you will be a sailor or a soldier boy like our Marcus.'

'I will be a sailor or a soldier and go adventuring,' I said.

'You are a very strange pair,' said Father, sighing. 'Now jump down and give me a little peace.'

'But you must tell us about the hospital, Father!' I demanded.

'Hetty, I don't know anything about the hospital. I've never even set foot inside it. I just know it's a good place for little children and you need never say you're ashamed to come from there,' said Father. 'Now stop plaguing me, girl. My head's aching.'

Father might never have been to this Foundling Hospital – but Mother had.

'Come with me, Gideon,' I whispered as Father sucked on his pipe and closed his eyes.

I tiptoed up the stairs, tugging Gideon behind me.

Rosie was guarding the door to Mother's bedroom, but I was bold.

'Father said we must talk to Mother,' I said.

I heard Gideon gasp at my outright lie. Rosie hesitated, but I pushed right past her determinedly. It was dark in Mother's room, the curtains drawn shut as if it was night-time. I could just make out the shape of Mother lying on her back. I wondered if she'd gone to sleep, but when I clambered carefully up onto the bed, her arm came out and held me tight. I hauled Gideon up too and he nestled on her other side.

'My lambs,' she murmured.

'Mother, Father has told us about the hospital. Is it truly a good place?' I asked.

I felt Mother stiffen. She swallowed hard. 'Of course it is a good place, Hetty,' she said.

I wondered if Mother could be a liar too. I lay thinking about it.

'Did Saul cry a lot when you said goodbye?' I asked.

Mother might be a brave liar, but she wasn't foolish. 'Yes, he cried,' she said.

'And did Martha cry too?'

'Yes, Martha cried too.'

'I shall cry,' Gideon whispered.

'I shall scream and kick and be so bad they won't let me stay, and then Mother can take me home,' I said.

5

I had loved Martha much more dearly than Saul but I had mostly forgotten her. However, I could not get Saul out of my head for months. I thought of him living in this huge hospital with so many other boys. I knew most boys weren't gentle and protective like my dear Jem. The village boys had often jeered and pointed at Saul, imitating the lopsided way he walked. One boy had pushed him hard and then laughed when he toppled over. I thought of all the foundling boys laughing and pointing and pushing Saul, and my eyes brimmed with tears.

Then I thought of all those boys mocking Gideon in turn. My fists clenched. I resolved to fight anyone who dared hurt my special brother. I was certain they would not dare hurt me. I was famous for my temper in the village. I might be the smallest but I was always the fiercest in any scrap. Mothers came and told tales to my mother about hair-pulling and kicking and sometimes outright punching. Poor Mother was mortified. She tried reasoning with me but I reasoned back.

'They called me names, Mother. Half-pint and Ginger and Runt. I said my name was Hetty and they just laughed. So I hit them and they stopped.'

'Jesus said to turn the other cheek,' said Mother.

Maybe Jesus wasn't teased the way I was. I thought hard, trying to remember the Bible stories I heard at Sunday school.

'God said, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,' I declared, imitating the solemn holy tone of the Sunday school teacher. I hoped it would make Mother laugh. I knew I was in danger of yet another paddling.

This suddenly started up a new fear.

'Do they punish the children at the hospital, Mother?'

'Not if they're good girls and boys,' Mother said.

This was not reassuring. I thought hard.

'Is that why they're there? Because they're bad?'

'No, no, no. It's because their own mothers can't look after them,' said Mother.

'Why can't they?' I asked.

Mother sighed. 'There never was such a girl for questions. You make my head ache, Hetty.'

'Please tell, Mother!'

'Well, dear, some ladies have babies and they can't look after them,' said Mother.

'Why can't they?' I persisted.

'Perhaps they're very poorly. Or they haven't got a dear husband like Father to give them a proper home. The ladies don't want to go into the workhouse' – Mother whispered the word and shuddered – 'so they take their babes to the Foundling Hospital.'

'Do they cry when they say goodbye?'

'I'm sure they cry a good deal,' said Mother.

'Did my first mother cry?'

'I'm sure it fair broke her heart to part with you, Hetty,' said Mother.

'Why can't I go and live with that mother now, Mother, instead of being sent back to this hospital? I don't need looking after. I can earn money. I could sing and dance so that people throw pennies at me.'

'You can't carry a tune to save your life, Hetty, so maybe they'd throw tomatoes,' said Mother. 'No dear, you don't belong to your mother now. You belong to the Foundling Hospital.'

I did not want to belong to an institution. I wanted a mother. I crept off by myself, squeezing into the tiny space at the back of the pigsty and the privy. It was private because everyone else was too small to squeeze through the gooseberry bushes and brambles to sit there. I wasn't comfortable because there were nettles and it smelled bad, but I didn't care. I pulled my skirts down over my bare legs, put my head on my knees and wept.

After a long time I heard them shouting for me. I stayed where I was. Then there were footsteps.

'Hetty? Hetty!' Jem called.

I did not reply to him, but I was sniffing hard.

'Oh, Hetty, I know you're in there,' said Jem. 'Come out. Please!'

I did not budge.

'I'm too big to come in and get you,' said Jem.

I heard the bushes rustling, then Jem swearing.

'That's a bad word!' I said.

'I know it's a bad word. Anyone would say it if they were scratched all over by brambles,' Jem panted. 'Do come out, Hetty.'

I simply wouldn't.

'Then I will have to try to get in,' said Jem, sighing.

He forced his way forward, thrusting his arm through the bushes until his hand j-u-s-t reached my bare foot. He held it tight. I curled my grubby toes into his palm.

'There now,' Jem whispered.

'Oh, Jem,' I said, sobbing.

'I can't bear you fretting about the hospital,' he said.

'I'm not going,' I said.

There was a silence as we held hand and foot.

'I think you have to go, Hetty,' said Jem. 'But perhaps I could go too. We'll pretend I am a foundling boy. Yes, I can take Gideon's place and he can stay with Mother.'

'Dear Jem! I wish you could. But Mother and Father wouldn't let you,' I said.

There was another silence.

'I will be so sad,' I said. 'I will have to stay there soooo long.'

Jem had taught me how to count to ten. I tried to count on my fingers.

'I will be there one two three . . . lots and lots of years,' I said dolefully.

'I think it is nine years, Hetty. And then you will be fourteen and quite grown up. And do you know what will happen then?'

'I will have to be a servant, and cooks will hit me and masters will kiss me,' I said.

'Maybe for a short while. But then I will come to fetch you and look after you, and as soon as you are old enough I will make you my wife. I know I am your brother, but not by blood so we can marry! We will have our own cottage and work on the farm and you will keep house and look after our babies. It will be just like our games in the squirrel house, but real, Hetty,' said Jem.

'Really real?'

'I promise,' said Jem.

I didn't always keep my promises, but Jem did. I seized his hand, kissed it passionately, and then crawled out of my hiding place to give him a proper hug.

Thoughts of the Foundling Hospital still

loomed, but at least I had a wondrous future ahead of me. I just had to wait one two three four five six seven eight nine years, endure a couple more while I dodged blows and kisses as a servant, and then I would be sweet sixteen and Jem's bride.

I dressed up in Mother's best white Sunday petticoat, clutching a posy of buttercups and daisies, and tripped around on Jem's arm, picturing for all I was worth.

'You are my lovely big handsome husband, dear Jem,' I said.

'You are my very fine little wife, dear Hetty,' said Jem.

The others laughed at us, especially Nat, but we didn't care. Gideon didn't laugh but he looked wistful.

'I want to be your husband, Hetty,' he said.

'No, Gideon, Jem has to be my husband, but you may come and live with us and be our big boy,' I said kindly.

I was out one day in the meadow playing Bride with my husband and big boy when I heard distant cheering and hurrahs, as if half the village were coming to applaud our marriage. I looked over the grass, squinting in the sunlight. I could see no one. They must be processing along the other side of the tall hedgerow.

Then I saw a gigantic grey head poking up above the hedge – a huge head with wrinkled skin and a tiny eye and the longest nose in all the world. I knew what it was!

'Oh my stars! E is for Elephant!' I gasped. 'There is an elephant walking along the lane.'

Jem was facing the wrong way. He did not take me seriously. 'Has it come to our wedding as a guest?'

'Don't picture T is for Tiger,' said Gideon. 'I don't like his teeth.'

'I'm not picturing! The elephant is real,' I said, tugging at them. 'Look!'

They turned and saw the head bobbing along above the hedgerow for themselves. Jem shouted, Gideon shrieked.

'Come on, let's see it properly,' I said, grabbing their hands.

'No, no, it will eat us!' Gideon cried.

'Don't be such a baby. Come on,' I commanded.

Jem and I hauled him along between us. We ran diagonally across the meadow towards the stile. The clapping and cheering grew louder, the vast head more wondrous the nearer we got.

We Are the Beaker Girls

We Are the Beaker Girls The Monster Story-Teller

The Monster Story-Teller The Worry Website

The Worry Website Girls Under Pressure

Girls Under Pressure Little Darlings

Little Darlings Clover Moon

Clover Moon Paws and Whiskers

Paws and Whiskers Dustbin Baby

Dustbin Baby Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays

Jacqueline Wilson's Happy Holidays Katy

Katy Lizzie Zipmouth

Lizzie Zipmouth Cliffhanger

Cliffhanger Vicky Angel

Vicky Angel Diamond

Diamond Love Lessons

Love Lessons My Mum Tracy Beaker

My Mum Tracy Beaker Lola Rose

Lola Rose Jacky Daydream

Jacky Daydream Green Glass Beads

Green Glass Beads The Story of Tracy Beaker

The Story of Tracy Beaker Clean Break

Clean Break Longest Whale Song

Longest Whale Song Little Stars

Little Stars Double Act

Double Act The Suitcase Kid

The Suitcase Kid Twin Tales

Twin Tales Girls in Tears

Girls in Tears The Dare Game

The Dare Game Diamond Girls

Diamond Girls Starring Tracy Beaker

Starring Tracy Beaker My Sister Jodie

My Sister Jodie The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch

The Dinosaur's Packed Lunch Candyfloss

Candyfloss Opal Plumstead

Opal Plumstead The Cat Mummy

The Cat Mummy Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday

Werepuppy and the Werepuppy on Holiday Hetty Feather

Hetty Feather Butterfly Beach

Butterfly Beach Midnight

Midnight How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub)

How To Survive Summer Camp (ePub) Cookie

Cookie The Worst Thing About My Sister

The Worst Thing About My Sister Bad Girls

Bad Girls Rent a Bridesmaid

Rent a Bridesmaid Girls in Love

Girls in Love The Mum-Minder

The Mum-Minder Rapunzel

Rapunzel Lottie Project

Lottie Project Best Friends

Best Friends Video Rose and Mark Spark

Video Rose and Mark Spark Glubbslyme

Glubbslyme Girls Out Late

Girls Out Late Big Day Out

Big Day Out Mark Spark in the Dark

Mark Spark in the Dark Buried Alive!

Buried Alive! Four Children and It

Four Children and It The Butterfly Club

The Butterfly Club Rose Rivers

Rose Rivers Lily Alone

Lily Alone Take a Good Look

Take a Good Look My Secret Diary

My Secret Diary Kiss

Kiss The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker

The Jacqueline Wilson Christmas Cracker The Worry Web Site

The Worry Web Site Emerald Star (Hetty Feather)

Emerald Star (Hetty Feather) The Bed and Breakfast Star

The Bed and Breakfast Star Sapphire Battersea

Sapphire Battersea Cat Mummy

Cat Mummy Sleepovers

Sleepovers Dare Game

Dare Game The Illustrated Mum

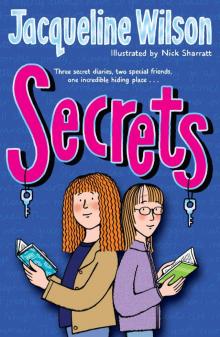

The Illustrated Mum Secrets

Secrets